Responding to COVID as a Mental Health Funding Organization

The lack of information around COVID-19 as well as an unplanned lockdown starting on March 24th significantly raised levels of distress across India — in particular, among vulnerable and marginalized communities. This distress was further compounded by other stressors related to food, livelihood, shelter, safety and basic survival. At least 200 deaths accounted for thus far (during the lockdown) were related to exhaustion, hunger, denial of medical care and suicides due to lack of food/livelihood, alcohol withdrawal or fear of having contracted COVID-19. Coronavirus is thus not just a public health issue, but also an issue of livelihoods, food security, shelter and justice.

MHI's COVID Response

Not Just a Health Crisis

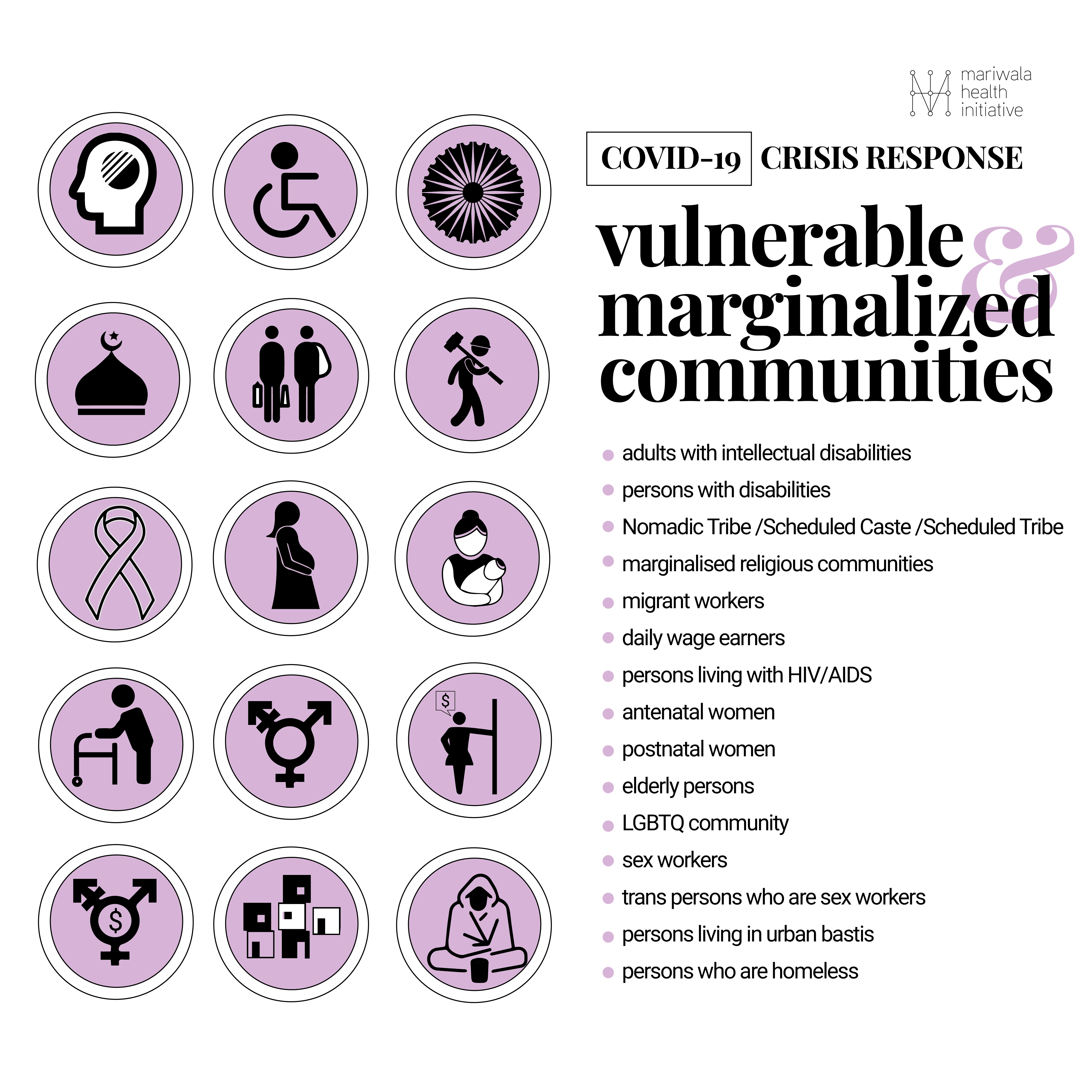

Therefore, as a mental health funding organization, we felt that our response to this crisis couldn’t simply be only providing mental health services. We see mental health as a development issue, thus, believe a response to COVID must address humanitarian needs especially for marginalised communities. Since our approach to mental health is psychosocial, it meant developing an inter-sectoral approach, with multiple agencies involved, and various levels of support - basic services such as food, shelter, physical health care, medication and mental health interventions for marginalised communities. MHI’s COVID-19 crisis response has therefore been directed towards supporting migrant workers, daily wage labourers, persons with disabilities, adults with intellectual disabilites, homeless persons, persons belonging to Adivasi/Tribal/Dalit communitites, persons living with HIV/AIDS, sex workers, widows, orphans and persons belonging to the LGBTQ community.

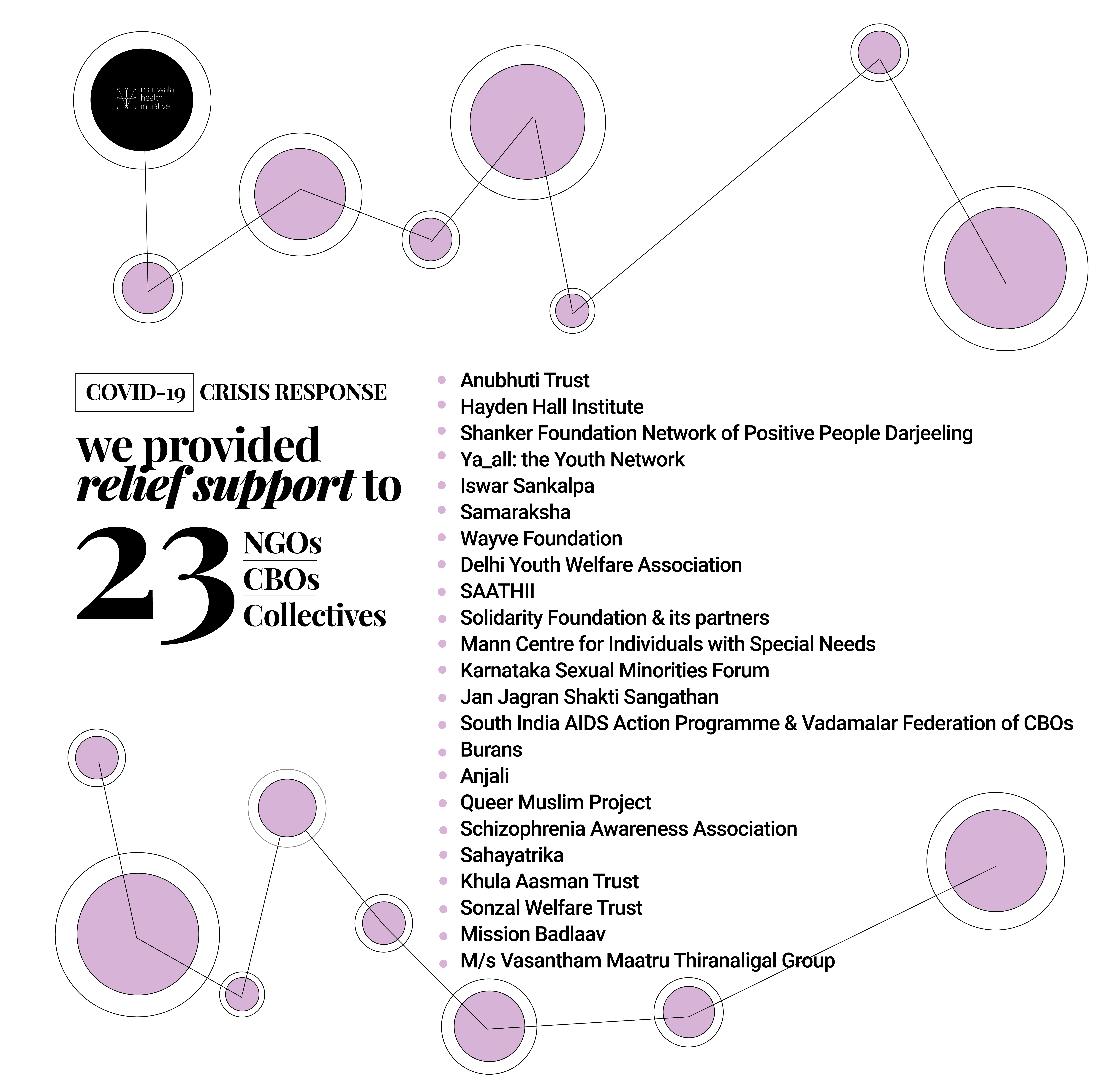

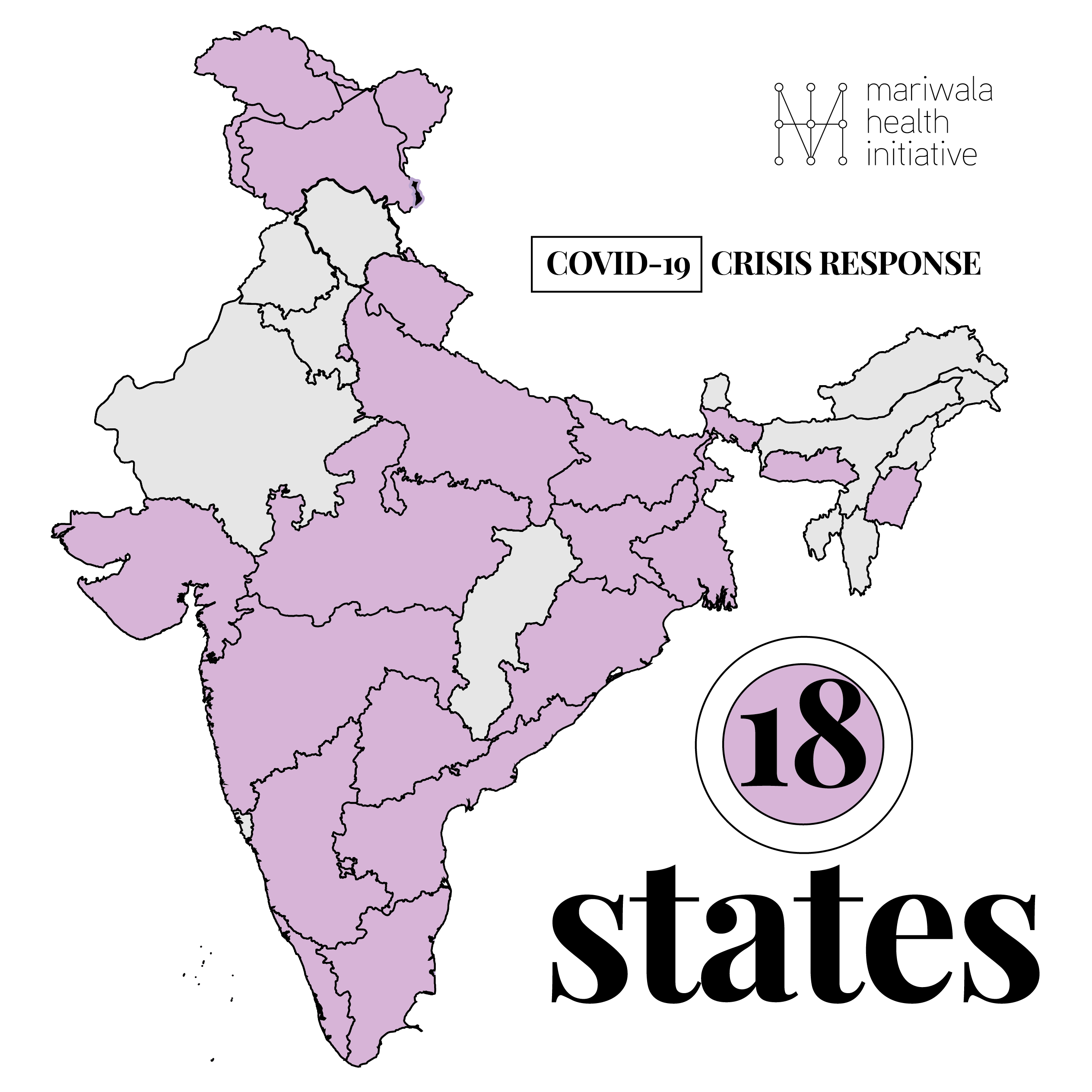

We have thus far partnered with 23 community-based organizations and collectives from 18 states across the country. We particularly made efforts to direct funds towards grassroots, community-based organizations, and tapped our existing network of partners across the country for recommendations and connections. Central to this is the idea that fostering a community’s ability to manage distress using its own resources is a sustainable approach that will help us address not just the short term impact of COVID, but also the long term.

Funder Responsibilities During a Crisis

We strongly believe that during a crisis, funders can proactively facilitate the work of their partners through instituting changes in disbursement, approval and reporting procedures. Some of the measures that MHI took in this regard included:

-

Facilitating our partners’ work through the lockdown: We reached out to our partners individually, to extend support and discuss how MHI could enable their work through the lockdown — for example, by providing additional funding support, repurposing funds for COVID-related work, enabling technology upgrades, extending grant allotment periods, minimizing reporting formalities and fast-tracking approval processes for changes in program interventions. We also funded technology upgrades for our partner iCall, a national helpline that provides free counseling services, enabling their counsellors to work from home during the pandemic. We allocated funds for partners to create collaterals on COVID and the need for physical distancing.

-

Instituting program adjustments to meet ground realities: Given the immediate need for community-level disbursement of information on COVID-19 in a format that is accessible and contextual — MHI instituted adjustments to programs to meet ground realities. For example, we funded community-based educational programs on COVID-19 that were geared toward increasing awareness and influencing behavior change.

-

Encouraging other funders to follow suit: We reached out to other funders, requesting them to interact with grantee organisations in a similar ‘enabling’ manner and provide support. To facilitate this process, we shared an email template of our ‘letter to our partners’ — allowing other funders to ‘copy-paste’ portions of these directives into their own communication with grantees.

“COVID-19 is not just a public health issue, but also an issue of livelihoods, food security, shelter and justice.”

MHI's response to COVID

Facilitating Virtual Mental Health Care Services

Enhanced levels of distress on account of the humanitarian crisis, combined with a lack of face-to-face sessions by mental health professionals (primary modality for the Indian context), has resulted in a severe shortage of mental health care services. However, several mental health professionals expressed interest in volunteering their services. Therefore, in partnership with iCall, we set up helplines in multiple languages — tapping this cadre of mental health professionals. Keeping in mind that providing mental health services virtually or over a phone, could be challenging for professionals used to face-to-face sessions — we are working with iCall to provide free webinars for mental health professionals on effectively providing counselling via phone, chat or video.

We also recognize that the current shortage of mental health care services cannot be addressed by trained mental health professionals alone. Therefore, in partnership with the Centre for Mental Health Law and Practice, we are working towards offering webinars on ‘psychosocial first-aid training’ in the context of COVID, for lay persons. MHI as part of its own work around marginalisation specifically designed webinars for communities uniquely affected by COVID-19 — namely Tuberculosis survivors and peer support during COVID for persons from the LGBTQ+ community.

Looking ahead: long-term impact of COVID-19

We estimate that mental health concerns will be further heightened in the medium and long term. Therefore, we are in the midst of discussion and strategy planning for medium and long-term challenges related to COVID-19 with a coalition of mental health organisations, representing all the major regions in the country. With this, we hope to prepare ourselves to build capacity and streamline implementation and research around COVID-19 in 2020-2021. With stronger links to communities on the ground, we also hope to work on not just mental health advocacy but structural and systemic responses to issues of economic insecurity and instability related to COVID over the next few years.