Therapy as a Tool in Dismantling Oppression

The Eurocentric model of mental health tends to be deficit-based, and uses diagnostic labels to describe a user who, in turn, is expected to be “treated” by an apolitical, value-neutral and ahistorical therapist. Consistent with the writings and activism of its founder, Latin-American social psychologist Ignacio Martin-Baro,(2) liberation psychology runs counter to the kind of “neutrality” typically adopted by mainstream Eurocentric MH practices. Therapists(3) must strive to understand injustice and oppression, and be explicit about their stance against these. When MH theory meets liberation psychology, therapists can influence and change systems that are unacceptable, as opposed to adapting to systems because they are typical. Within the framework of feminist therapy, for instance, a survivor of domestic violence is supported in seeking a life free from violence. The therapist, then, adopts an explicit position by communicating that violence is unacceptable, and that responsibility for violence lies with the perpetrator.

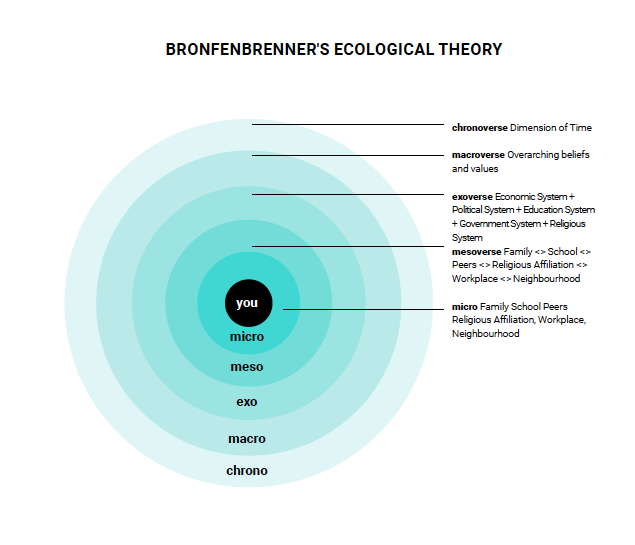

A liberation(4) psychology framework acknowledges a multilayered ecosystem. According to Urie Bronfenbrenner who originally proposed this ecological framework in the ’70s, an individual is embedded in a microsystem (family, friends, work, school, and so on), a mesosystem of relationships within their microsystem (such as the relationship between family and work), an exosystem that indirectly impacts them (the physical environment) and a macrosystem of cultural attitudes and ideologies (casteism, for instance, or patriarchy). Revisions of the model included a chronosystem (lifelong events, historical events). Oppressive ideologies maintain structural inequalities through their influence over the macrosystem and exosystem: casteism makes it harder for people to access education and safe livelihoods; Hindutva homogenizes neighborhoods by preventing religious minorities from living there.

Mainstream therapy, which focuses on surviving the trauma of the ecosystem, and prioritizes individualistic emotion along with problem-focused strategies of coping, might lead to a counter-productive response to oppression, one that implicitly blames the victim—as with failure seen as a result of not trying hard enough. When the focus of change is limited to the individual’s microsystem, therapy risks becoming a tool for people to adapt to their oppression by either denying the influence of this oppression or disengaging from it.(5) A therapist’s silence around oppressive systems that impact the user reflects such denial and disengagement while, significantly, avoiding discussion of how the therapist’s own privilege impacts the therapeutic relationship. Problem-focused strategies of coping, such as compensation and empowerment, also prioritize an oppressive system at the cost of those trying to survive it, for instance Dalits working doubly hard to get what a Savarna has by virtue of unearned caste privilege.

I propose a liberatory therapeutic framework in which the therapist would collaborate with the user to get in touch with feelings that highlight how their ecosystem traumatizes them and how it undercuts their sense of agency. Secondly, the therapist would use a strengths-based lens to celebrate resilience, and amplify the user’s efforts to advocate for change as well as develop stamina for the process of sociopolitical change. Such therapy would be embedded in a feedback-informed framework where the therapist and user are both experts who co-create healing by developing a vision for change. The therapist is the MH expert, whereas the user is the expert of their own experience. The therapist actively seeks feedback from the user about their therapeutic alliance, and facilitates therapy accordingly. Additionally, the therapist vocalizes a commitment to liberatory/anti-oppressive values through messages within and beyond the clinic, through, say, an engaged social media presence, or active collaboration with organizations that address structural inequalities.

In my therapeutic work I also integrate a toolkit for people of color(6,7), a line from which is central to my work: ‘The system does not get to determine your worth, dignity and humanity.’ These words serve as a reminder to create space between one’s self-concept and the messages communicated by oppressive systems, thus protecting oneself from internalizing oppressive messages while persevering towards liberation.

BRONFENBRENNER'S ECOLOGICAL THEORY

Liberatory framework in action

A 23-year-old cisgender Sikh-American woman presented with anxiety about failing medical school due to her inability to focus on her studies.(8) During our sessions she processed how classroom discussions about health disparities perpetuated racial stereotypes, and the similarity between the racist assumptions made by her classmates and by other healthcare professionals. While she experienced rage, her professor and classmates upheld an “objective” (read: devoid of feelings) stance, rendering her mute and making her question whether she could succeed in medical school if “mere class discussions” affected her in this way. Validating her rage created a safe space for her to acknowledge the impact of racial microaggressions. I invited her to use her feelings as feedback about her values. Actively celebrating her family’s excitement and support around her career goals, and recalling her ancestors who had not had the opportunities she did, added a greater sense of meaning to her education and enlarged her perspective in ways that acknowledged racism but did not center it. She articulated the hope for better discussion about health disparities, and a vision for working towards an equitable healthcare system. We discussed ways she could connect with professionals who shared her vision and might serve as role models. Our collaborative therapeutic work is focused on supporting the steps she takes towards a career in healthcare, ensuring that instances upholding white privilege do not lead her to question her own values and dreams.

Therapy as a radical act of self-care

A liberatory framework could make therapy more relevant to communities that are, otherwise, silenced by an MH framework that pathologizes their valid response to oppression. For instance, a strategy like mindfulness can help restore communities fighting oppression by centering their voices in the research and development of mindfulness curricula.(9) Correspondingly, privileged communities could use such emotion-focused strategies to build their stamina for listening to, rather than disengaging from, the impact of oppression. For instance, Savarna privilege continues to be deeply embedded in the Indian context (including the diaspora), and liberation from the caste system requires Savarnas to respond to feedback with readiness for change.

Therapy can be geared towards thriving, alongside fighting oppression. A liberatory framework allows the celebration of joys and strengths associated with one’s community and takes it beyond the trauma-focused lens within which it is otherwise framed. As Audre Lorde(10) puts it, ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.’ In the face of ideologies that prioritize the perceptions of the privileged and delegitimize the experiences of the oppressed, entering a therapeutic space that validates and even celebrates liberation becomes a radical act.

Click here to download the full version of ReFrame III

“Problem focused strategies of coping, such as compensation and empowerment, also prioritize an oppressive system at the cost of those trying to survive it.”

References

[1] French, B. H., Lewis, J. A., Mosley, D. V., Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Chen, G. A., & Neville, H. A. (2020). Toward a psychological framework of radical healing in communities of color. The counseling psychologist, 48(1), 14-46. https://doi. org/10.1177/0011000019843506

[2] Ignacio Martin-Baro was a Spanish-born Jesuit priest trained in psychology at the University of Chicago. Through his writings and activism Martín-Baró devoted his career to making psychology relevant to the community and the individual. During the Salvadoran Civil War, he was killed by the Salvadoran army in November 1989.

[3] Martin-Baro explicitly named Psychologists; I use this broader term instead, to include a range of disciplines.

[4] I strive to use the term “liberation” instead of “antioppression” throughout this paper, analogous to using a strengths-based framework over a deficit-based one.

[5] Phillips, N.L., Adams, G., & Salter, P.S. (2015). Beyond adaptation: Decolonizing approaches to coping with oppression. Journal of social and political psychology, 3(1), 365-387. doi:10.5964/jspp.v3i1.310

[6] This toolkit is embedded in the sociopolitical context of the United States, where people of color and the indigenous community experience oppression on the basis of race, gender, immigration status, intergenerational trauma. My (evolving) manifesto is further informed by my experiences as a therapist, therapy user and an immigration activist in the US.

[7] Adames, H. Y. & Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y. (2017). Surviving & resisting hate: A toolkit for people of color. IC-RACE. Retrieved April 27th, 2020 from https://icrace. files.wordpress.com/2017/09/icrace-toolkit-for-poc.pdf

[8] To protect confidentiality, this user experience is a fictionalized version of a similar experience.

[9] Black, A. R. (2017). Disrupting systemic whiteness in the mindfulness movement. Mindful. Retrieved April 27th, 2020 from https://www.mindful.org/disruptingsystemic- whiteness-mindfulness-movement/

[10] Lorde, Audre. (1988). A burst of light and other essays. Ithaca, N.Y.: Firebrand Books,