Teachers as Agents of Change

‘What help can I give? We know how

hard she is working...’

‘The people who are helping the

children are more learned than us.’

— PARENTS

Many primary school teachers already support students with MH difficulties and significant behavioural challenges. While the intervention discussed here shifts care to a community-based setting, it remains embedded within the school as an institution. Understanding how power operates within the school, and in the community, is key to our evaluation of this intervention.

The intervention

Tealeaf: Mansik Swastha (Tealeaf) reimagines MH care for primary school children by integrating it into teacher workflow. Appropriate MH care for younger children can help to build their social and emotional life skills, support future mental well-being, and may reduce the extent of future disability. Evidencebased therapy lies at the core of this intervention, guided by the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program.(1) By incorporating targeted MH care for students throughout the day, the care becomes ongoing, situated and community-based, rather than being provided only in expert-led, clinical settings.

A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of this intervention is under way, along with an embedded ethnographic study of process.

context

Darjeeling is a geographically and ethnically distinct part of West Bengal – its only hilly region. Most, but not all, aspects of state administration fall under the separate authority of the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration. Regional marginalization, the complex governance structure, and the absence of Panchayati Raj institutions bring challenges in the implementation of development schemes here.

Tealeaf is being implemented in 20 rural low-cost private schools, expanding to 60 schools by 2022. We have chosen to work in private schools, given their increasing role in the education sector. These schools fulfill education needs and aspirations in rural areas where government schools are distant, or not functioning well. Official data on Darjeeling is sparse, but our experience suggests that private school enrolment is at the high end of the nationally estimated range of 30% to 50. (2,3) Additionally, private schools are excluded from existing school health interventions, with teachers having little access to ongoing training and support. Thus, their students are at risk of being left behind.

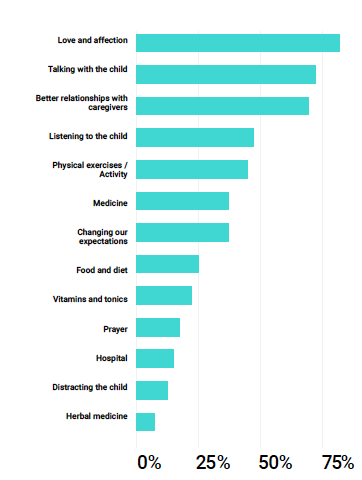

Teacher knowledge and attitudes about mental health

The majority of teachers who attended our one-week training in 2020 believed that both school and community had a role to play in managing MH challenges. They were clear that such care should not be confined to far-off “experts”, and that families should not have to manage without support. The teachers’ top four ranked responses about what helps children with MH health care needs were all relation- and interaction-based, rather than deriving from a medical understanding, as in the graph seen to the left.

Only a small minority of training participants (7%) felt that the role of certified professionals was crucial. The larger recognition of the importance of community support, on the other hand, has been extremely encouraging. Training participants saw their teaching role as one of community service or social work. These teachers are poorly paid, most earning Rs 1,500 to Rs 3,000 monthly.

“In becoming delivery agents of MH care, teachers must renegotiate existing dynamics while gaining a better understanding of their multiple, intersecting positionalities and roles.”

Tealeaf: Mansik Swastha (Research Data)

Mental health care

While the Tealeaf intervention shifts care delivery to a community-based setting, it remains embedded within institutions that have their own power dynamics: between teachers and children; teachers and parents; teachers and school principals.Care plans depend on teachers and parents co-operating to achieve the best outcome possible for children in the program. Yet the traditional perception of teacher as “expert” does not necessarily align with a collaborative approach to MH care. Teachers, too, may have their own biases and assumptions, which need to be challenged if they are to effectively support children and deliver this type of care. power structures and class dynamics

Despite their willingness to support children and families, and their view of themselves as “social workers”, teachers inevitably have a culturally situated position of authority.(4) When sharing their experiences, they described a clear social distance between themselves and their students' families. Even the language that teachers use is typical of the ways in which the Darjeeling middle class distinguishes itself from the less educated, or those seen as less sophisticated.(5) Teachers often had the impression that parents did not care or were not interested in their child’s education. ‘Parents feel that sending their child to the school is their only responsibility, and after that the teacher is supposed to take care of everything.’

What teachers perceived as a lack of care, or disinterest, was in many instances an expression of trust in the teacher’s abilities. Parentswho were not highly educated felt themselves ill-equipped, and were handing all responsibility for their child’s development over to the school. By encouraging relationships based on shared goals of supporting and caring for the child, such gaps between teachers and parents may be minimized. While parents might view teachers as the ultimate authorities regarding their child’s education, teachers are often disempowered within the school environment, subject to the strict control of school owners and principals. Some teachers were actively discouraged from communicating with parents. In becoming delivery agents of MHcare, teachers must renegotiate existing dynamics while gaining a better understanding of their multiple, intersecting positionalities and roles.

unlocking change: improved relationships

Changing language used, establishing new relationships and challenging bias cannot all be accomplished in a one-week training. Ongoing mentorship and support is, then, a core component of Tealeaf. Workshops with principals and parents also help to bridge gaps. By modelling supportive behaviour and good communication skills, and providing suggestions for parent interactions, Tealeaf initiates a larger shift in relationships in the wider community. Following the intervention, a teacher explained how her perspective about a child’s challenging behaviour changed:

‘. . . we realized that we need to observe and find out the root cause for the (child’s) behavior. . . we got to know that the child couldn’t do the homework or study at home because there was no electricity at home. This way we became aware.’

With improved communication, parents feel more empowered to engage with the school, and teachers to empathize with the complex challenges faced by the children and their families – thus being better placed to understand the links between child behaviour and mental health.

conclusion

Task-shifting MH care to classroom teachers is a potentially powerful approach to embedding such care in the school and community, and closing the care gap by providing children with the much-needed MH support they may not otherwise receive. While teachers are trained to identify, and provide targeted support to, children showing signs or at risk of mental distress, it is evident that these skills are already being used more widely – increased community engagement and relationship-building have already extended far beyond those children receiving targeted support.

Over the next three years, our documentation and analysis of this intervention will further explore how differences in power, including those related to class, status, age and gender, impact its effectiveness. ¤

Click here to download the full version of ReFrame III

References

[1] https://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/e_ mhgap/en/

[2] Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2018. http://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202018/ Release%20Material/aserreport2018.pdf

[3] Unified District Information System for Education 2016-2017, DISE 2018. http://udise.in/Downloads/ Publications/Documents/Flash_Statistics_on_School_ Education-2016-17.pdf

[4] Sriprakash, A. (2009). ‘Joyful Learning’ in rural Indian primary schools: an analysis of social control in the context of child‐centred discourses. Compare, 39(5), 629-641.

[5] Brown, T., Ganguly-Scrase, R., & Scrase, T. J. (2016). Urbanization, rural mobility, and new class relations in Darjeeling, India. Critical Asian Studies, 48(2), 235-256.