Mental Healthcare is Incomplete without the Body

introduction

The body – a place where the brain and perhaps the mind reside, is but a rare guest in therapeutic spaces, knocking on the door only lightly when asked, ‘Where do you feel that in your body?’ When the body is brought up in mental healthcare, it is when something goes “wrong” with its functioning, as a “product” seeking perfection; or as a “token” of diversity and charity. In the battle against the systemic inequalities that perpetuate mental health concerns, the role of the body – as a recipient and as a tool of structural oppression and social marginalization – is invisible, much like the bodies of the oppressed. This article emphasizes that ignoring and overlooking the body is a structural phenomenon within mental healthcare, and highlights its relevance using insights from our way of practicing dance/movement therapy (DMT), called the embodied systems approach (ESA).

bodily oppressions and mental distress

Different systems might use the body as a basis for oppression and violence, with some systems finding structural support for cementing and legitimizing such acts. A glaring example is that of laws that require bathrooms to be made available for only two of the biological sexes, and used according to sex assigned at birth. Other examples (from among many) include: discrimination rooted in a combination of colourism and casteism; public infrastructure that is not accessible to people living with various disabilities; barring entry of menstruating people from religious sites and some physical spaces in homes; an arranged marriage process that prioritizes bodily features; and judgements regarding the "wholeness" of a person based on challenges with conceiving a child, or on their choice not to have one. The body might also be the site where oppression and violence are experienced, in ways that include: normalization of corporal punishment for children; harassment based on sexual orientation, and gender identity and expression; domestic violence in the form of physical and sexual abuse; customs such as expecting a widow to live with a shaved head after the death of her spouse.

With work being a key part of many people’s lives, the stigmatization of some professions involving the body can also contribute to mental distress. Sex workers, construction workers, sanitation workers, performing artists, and sportspersons, all integrate body actively into their work, but are placed at different points along a moral hierarchy of professions. Financial stability, access to healthcare, and even dignity/respect extended to a person (all of which could impact mental health), may depend upon whether these professions are celebrated or condemned.

Other forms of distress directly pertaining to the body, such as chronic pain or illness, eating disorders, health-related anxiety, and health conditions and disabilities that are not externally visible, can affect mental health as well. Even commonly recognized psychological needs in mental health practice today, such as emotional expression/regulation, processing trauma, or coping with the stress evoked by a productivity-focused culture, all have body-based components.

the body in the Indian mental health field

All people, including healthcare professionals, hold perceptions and beliefs about their own bodies and the bodies of “the other”, which create thought-based and non-verbal biases in our clinical practice and personal lives. The various factors at play here may include (but are not limited to) family, religion, caste, body type and ability, sexuality, gender identity and expression, education, class, geography, occupation, and language. It is essential, both in clinical and reflexive practices, for healthcare professionals to explore the intersection of these factors, the systemic baggage that each body bears, and the structural treatment of different bodies.

The body and mental health share a bi-directional relationship. Yet many therapeutic frameworks fail to integrate the two clinically. It is important to acknowledge that body-based practices such as yoga, meditation, and breathwork, do exist and are being consciously integrated into the conceptualization of mental health in India. While psychology, at large, seems to adopt a mind-over-body approach, these practices lean more towards a body-over-mind approach. The former creates space for verbal rather than experiential processing, whereas the latter focuses primarily on the physical manifestations of mental health needs without necessarily addressing their origins. There is a need for a body-and-mind approach that taps into the vital interplay between them in a more balanced way. For mental health professionals, this means acknowledging and working with genetic influences, psycho-neurophysiological functions, body memory, body language, and movement-based responses and coping skills. Not to include the body in mental healthcare services or training is to dismiss a whole part of a person’s being.

Illustration: Studio Ping Pong

an embodied systems approach to mental healthcare

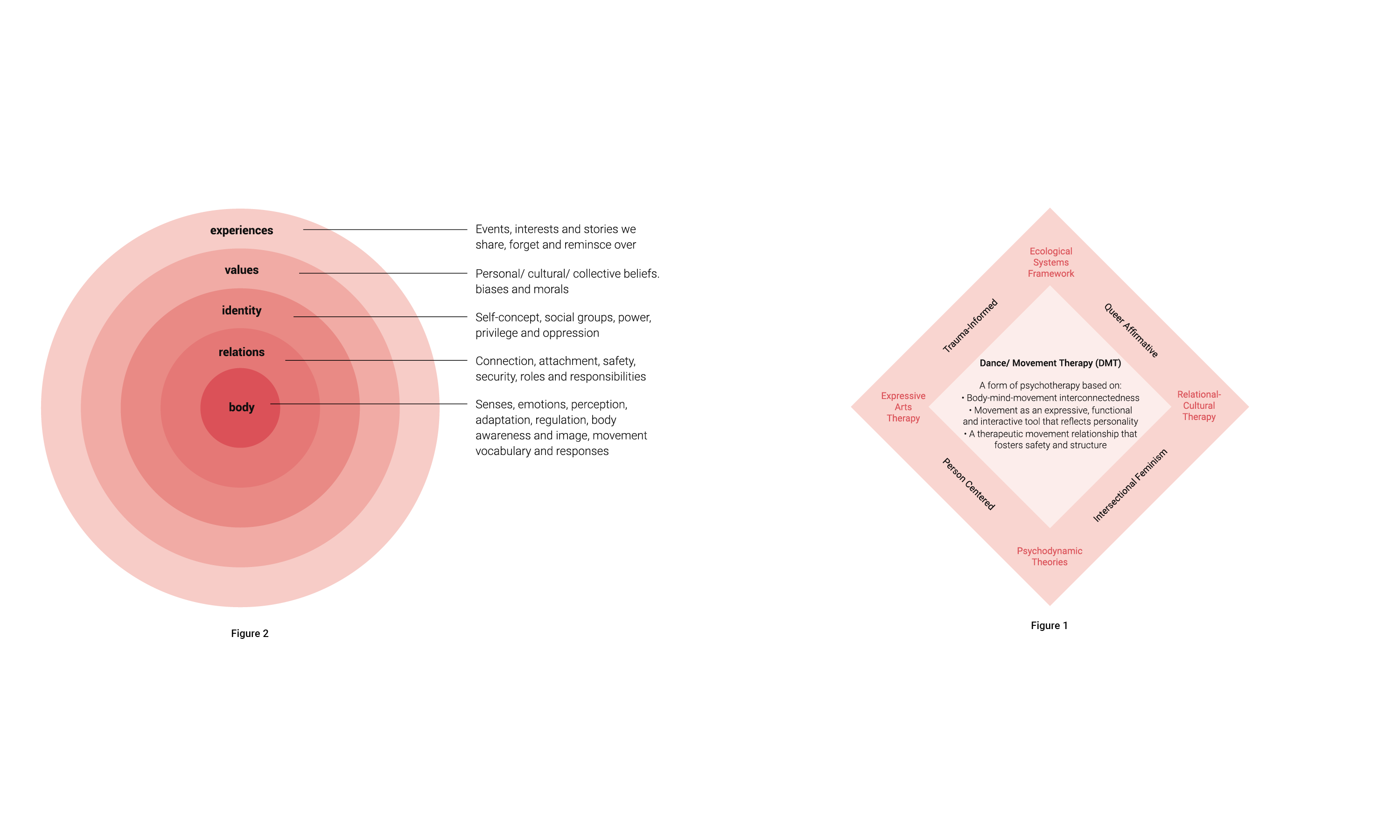

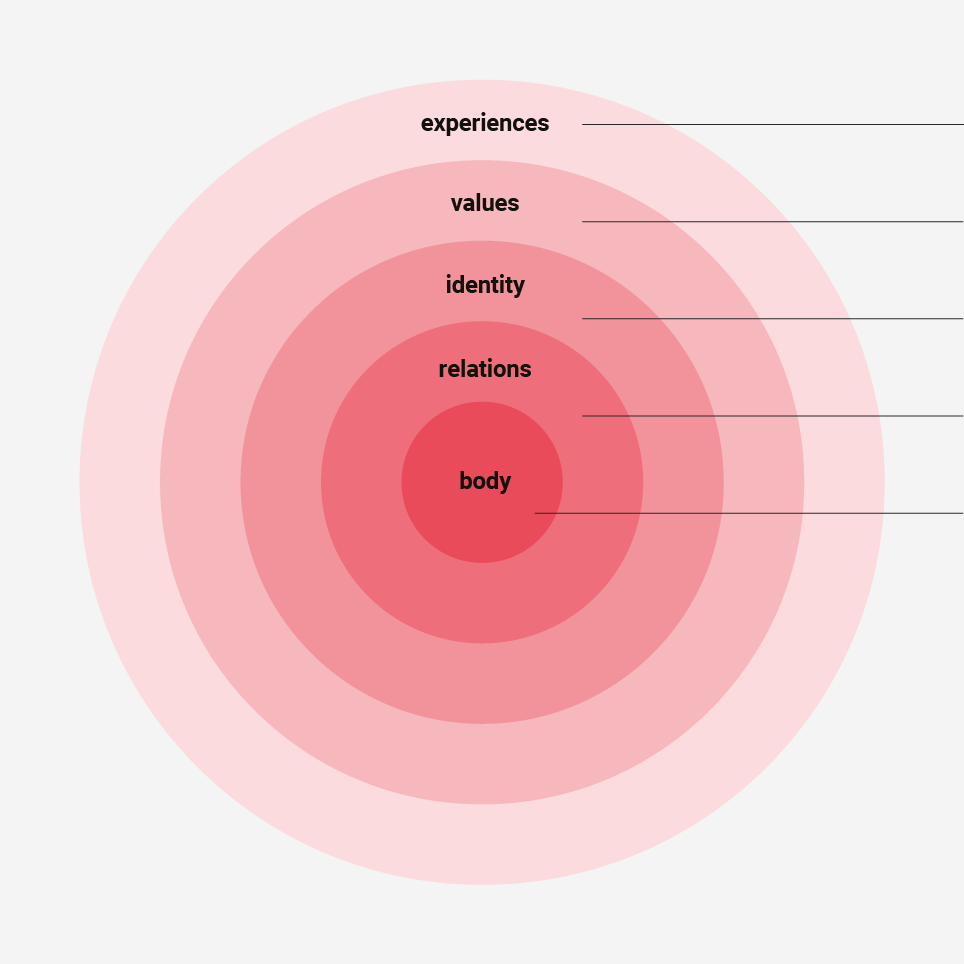

In conversations on factors affecting mental health, the most immediate system available to us – the body – is rarely recognized as a system in itself. Discussions on how the body and its movements appear, experience life, and respond, within various systems, are even rarer. ESA recognizes the body as a system which is as relevant as the others. Alongside the ecological systems framework and relational-cultural therapy, DMT, expressive arts therapy and psychodynamic theories also serve as cornerstones of ESA. Their integration into the services offered, and the processes that support the functioning of the organization (such as training of clinicians, documentation, terms of employment/internship), is further informed by an intersectional feminist lens, a queer affirmative stance, and trauma-informed and person-centered approaches (see Figure 1).

“Other forms of distress directly pertaining to the body, such as chronic pain or illness, eating disorders, health-related anxiety, health conditions and disabilities that are not visible can affect mental health as well.”

Figure 2

Drawing upon the aspects depicted in the wheel illustrating ESA (see Figure 2), the trained clinician is able to attune themselves to clients and to support them in ways that are congruent with the approach, which allows for an expansion of body-mind awareness, and facilitates shifts in people’s relationship with their bodies and mental health. Further, bodies can carry shame, which may present as minimization of posture, gestures, space taken, and so on. When holding and moving shame from an ESA perspective, people can experience body autonomy and vitality in the freedom scaffolded by movement interventions.

ESA in practice: brief examples from therapy sessions

In a therapy session, integration of ESA could present as a couple using their walking styles as a step towards uncovering how expected gender roles in a heterosexual, Hindu marriage in Indian society may be shaped by developmental experiences like co-regulation of emotions, and power dynamics within family-of-origin based on the intersection of gender and age. Another example supports insight into family structure through an intervention: a family attempts to maintain balance while leaning on a circular stretch-band, prompting a conversation on roles within the family – who “provides support”, and who “throws the family off-balance”. Also, through ESA, when dancing in synchrony with the therapist, a queer client became aware of an asynchronous workplace interaction. The therapist encouraged a further exploration of that interaction, which the client eventually identified as being one of passive body-shaming.

In each of these instances, leaving the body or other systems out of the session would have kept significant insights at bay. While only three examples have been given here, our experiences continue to confirm that mental healthcare led from a body-/movement-informed lens alongside a systems lens allows for a somatic awareness, as well as validation of an individual’s bio-psycho-socio-relational-cultural experiences. It brings to life the idea that a solely cerebral/cognitive approach can be restrictive since ‘our minds are [just] one thing our body does.’

Click here to download the full version of ReFrame IV

Editorial Note:

The Reframe Editorial team was very saddened to hear that Aditi Trivedi, one of the co-authors of this article passed away in September. We would like to acknowledge Aditi's work as a therapist and as a professional in the dance/ movement therapy space in India. Please do visit her Instagram page @breathflowmovement on which she has shared her wisdom as a dance/ movement therapist.

_________________________________________________________________________

References:

(1) Vamos, Marina. "Body Image in Chronic Illness: A Reconceptualization." The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, vol. 23, no. 2, 1993, pp. 163-178.; Goodill, Sharon W. “Dance/Movement Therapy for People Living with Medical Illness.” Advances in Dance/Movement Therapy: Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Findings, Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH, 2006, pp. 52–60.

(2) Krantz, Anne M. "Growing into Her Body: Dance/Movement Therapy for Women with Eating Disorders." American Journal of Dance Therapy, vol. 21, no. 2, 1999, pp. 81-103.; Feldman, Yeva. "Gestalt and Dance Movement Psychotherapy in Adults with Eating Disorders: Moving towards Integration through Practice and Research." Essentials of Dance Movement Psychotherapy: International Perspectives on Theory, Research, and Practice, Routledge, 2017, pp. 83-97.

(3) Roberts, Nell G. "Embodying Self: A Dance/Movement Therapy Approach to Working with Concealable Stigmas." American Journal of Dance Therapy, vol. 38, no. 1, 2016, pp. 63-80, doi:10.1007/s10465-016-9212-6. Accessed May 2021.

(4) Berrol, Cynthia F. "The Neurophysiologic Basis of the Mind-Body Connection in Dance/Movement Therapy." American Journal of Dance Therapy, vol. 14, no. 1, 1992, pp. 19-29, www.springer.com/journal/10465. Accessed May 2021.; Homann, Kalila B. "Embodied Concepts of Neurobiology in Dance/Movement Therapy Practice." American Journal of Dance Therapy, vol. 32, no. 2, 2010, pp. 80-99, doi:10.1007/s10465-010-9099-6. Accessed May 2021.

(5) Dosamantes, Irma. "Body-image: Repository for cultural idealizations and denigrations of the self." The Arts in Psychotherapy, vol. 19, no. 4, 1992, pp. 257-267.; Pylvänäinen, Päivi. "Body Image: A Tripartite Model for Use in Dance/Movement Therapy." American Journal of Dance Therapy, vol. 25, no. 1, 2003, pp. 39-55, www.springer.com/journal/10465. Accessed May 2021.

(6) Birdwhistell, Ray L. "Body Motion." Kinesics and Context: Essays on Body Motion Communication, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970, pp. 183-191.; Knapp, Mark L., et al. Nonverbal Communication in Human Interaction. 8th ed., Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2014.

(7) Schmais, Claire. "Dance Therapy in Perspective." Focus on Dance VII: Dance Therapy, American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation & Dance/ National Endowment for the Arts, 1974, pp. 7-12.

(8) Caldwell, Christine. ADTA 52nd Annual Conference - Movement as Pathway to Neuro-Resilience and Social Connection: Dance/Movement Therapy at the Forefront". Bodyfulness: Dance/Movement Therapy and Contemplative Practice. Nov. 2017, San Antonio, Texas, 2017.