Making Your Days Matter, to the Very End

Introduction

An issue of ‘The Economist’(1) mentions a small Buddhist temple in a cherry tree-lined path in Tokyo, where prayers to baby Buddha ask for two wishes to be granted – a long, spry life, and a quick and painless death. A good life is often discussed; a good death rarely spoken about. The silence that surrounds conversations about how we pass on arises from our discomfort with confronting our own mortality, and uncertainty about where such conversations could lead. However, if quality of death indicators are to be believed, we don’t die very well in India. In its Quality of Death index,(2) a study of 80 countries ranked India among the 15 worst countries to die in – and yet, India has given the world one of the finest examples of quality palliative care at the community level, with the state of Kerala, which has a mere 3% of the country’s population, providing more palliative care services than the rest of India put together.

It is unfortunate – given the significant difference it can make to quality of life – that most people seek palliative care very late, because the concept is mistakenly associated only with end-of-life care. Besides, palliative care in India caters mainly to cancer patients, although it is well recognized that pain relief – physical, emotional, spiritual – can be provided for a wide spectrum of conditions, such as cardiac failure, neurological illnesses, and others.

The need for psychosocial support in home-based palliative care

At the core of palliative care lies the concept of total pain management. Going beyond physical pain, this approach recognizes that patients are not mere objects of ‘treatment’, but human beings who respond to compassion, heartfelt care, and the beneficial effects of affirmative beliefs. In India, although such services are still nascent, some of the most heartening initiatives may be found in the area of home-based palliative care. As a core member of a multi-disciplinary team that attends to the patient at home, the counselor’s role is seen to be transformative in many ways. Dr Armida Fernandez, former Dean, LTMG/Sion Hospital, and Founder, SNEHA, who set up a home-based program in Mumbai, avers that ‘physical suffering can be assessed and dealt with to a great extent with medications . . . however, psychosocial and spiritual suffering of both the patient and caregivers is more challenging; it often needs as much attention. Depression, anxiety, confusion, anger and frustration are some of the issues our counselors deal with (personal communication, June, 2020).

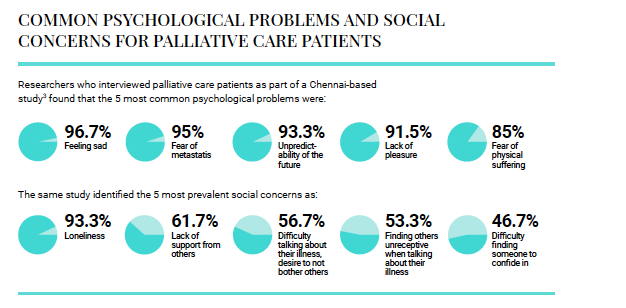

Researchers who interviewed palliative care patients as part of a Chennai-based study(3) found that the five most common psychological problems were, in descending order: a depressed mood (96.7%); fear of metastasis (95%); the unpredictability of the future (93.3%); not experiencing pleasure (91.5%); fear of physical suffering (85%). The same study identified the five most prevalent social concerns as: loneliness (93.3%); experiencing very little support from others (61.7%); difficulty in talking about their illness due to not wanting to bother others (56.7%); finding others not receptive when they spoke about their illness (53.3%); the difficulty of finding someone in whom to confide (46.7%).

COMMON PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS AND SOCIAL CONCERNS FOR PALLIATIVE CARE PATIENTS

Shifting focus: from the disease to the person

It is clear, then, that efforts to relieve distress cannot be complete without shifting the focus from the disease to the person. And this can best be done by empathetic listening, rarely possible in the environment of a hospital or OPD, where the pressure of waiting patients and the alienation of the surroundings can be overwhelming, both for the patient and for family members. Avani Bhatia (personal communication, June 15, 2020), consulting psychotherapist associated with the home-based care provided by Romila Palliative Care (Mumbai), shared her experience of working with terminally ill patients and their family members. A key turning point, she finds, is when denial changes to acceptance, leading to what she describes as ‘miraculous and peaceful transitions, and dignified dying’. Her role doesn’t end with the passing on of the patient; bereavement counseling is an important aspect of the care she then provides.

Tonia C Onyeka,(4) in a review of five cases of patients with cancer, reported that the cancer diagnosis is a situation that affects not just the patient but also family members and other caregivers, producing great degrees of psychosocial distress. It is not unusual for families to refuse to accept the diagnosis, or to keep hoping results were wrong. Avani Bhatia (personal communication, June 15, 2020) also spoke about engaging with the family of a young woman diagnosed with metastatic cervical cancer, where it took counseling over a long period of time for the patient, her husband and daughter to come to terms with the reality of the prognosis, and to open the door to palliative care services. The psychosocial support that the entire family then received made for a better management of physical symptoms as well as of the emotional turmoil that they were all experiencing, and ultimately for a peaceful and dignified passing.

Dr Jayita Deodhar (personal communication, June 15, 2020), Professor and Psychiatrist, ad hoc officer-in-charge of the Department of Palliative Medicine, Tata Memorial Hospital, offered her own insights on how the provision of psychosocial support in a home-based setting for palliative patients makes a marked difference, as compared to services in an out-patient department. She believes that a home care team visiting the patient in their own environment gets useful glimpses into the patient’s real-life situation – including caregiver burdens, family dynamics and other aspects of the home setting. The counselor is able to spend time on understanding and exploring patients’ care preferences, engaging with them in shared decision-making in their own milieu, such as planning and preparing for end-of-life care – as distinct from having such conversations in the artificial setting of the clinic, while also avoiding the need for seriously ill patients having to travel.

There is, however, another aspect to be considered, in the context of providing such services at home. As Dr Jayita (personal communication, June 15, 2020) explained, ‘Some challenges are quite unique to our social and cultural context. Our patients live in restricted space, sometimes within one room, leading to congestion and lack of privacy which is so important when one has to verbalize emotional concerns, fears and anxieties. Stigma is another barrier. Our patients have sometimes requested us to park our hospital vehicle at a distance from their home, so that neighbours don’t get to know that the doctor and nurse from the hospital are attending the patient, as ours is a well-known cancer hospital.’

Given the value of psychosocial support in home-based palliative care programs, we need to keep working to generate awareness about such services, and highlighting the quality outcomes they can provide. And this has to be done across all stakeholders, not just patients and families but also, importantly, healthcare practitioners themselves, who often need to be reminded that when there’s no cure, the task hasn’t ended; there is always care that can, indeed must, be provided.

Click here to download the full version of ReFrame III

“The psychosocial support made for a better management of physical symptoms as well as of emotional turmoil, and ultimately for a peaceful passing”

[1] End-of-life care A better way to care for the dying. (April, 2017). The Economist. Retrieved from https:// www.economist.com/international/2017/04/29/abetter- way-to-care-for-the-dying

[2] Economist Intelligence Unit. (2015). The 2015 Quality of Death Index. Retrieved from https://www.apcp.com. pt/uploads/2015-EIU-Quality-of-Death-Index-Oct-6- FINAL.pdf

[3] Mithrason, A., Parasuraman, G., Iyer, R. and Varadarajan, S., 2018. Psychosocial problems and needs of patients in palliative care center. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health, 5(4), p.1385.

[4] Onyeka, T. (2010). Psychosocial issues in palliative care: A review of five cases. Indian Journal Of Palliative Care, 16(3), 123. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.73642