The ideal of ‘Recovery’

What does care look like?

A Psychosocial Model of Mental Health Care

I am bipolar. Within a psychosocial paradigm one may iterate this as having a psychosocial disability, or living with a diagnosis. In a medicalized framework, I have a ‘disorder’. I am something that requires ‘fixing’: a pathology-based intervention to make me ‘orderly’, to make me conform to a normative understanding of what it means to have a mind at all.

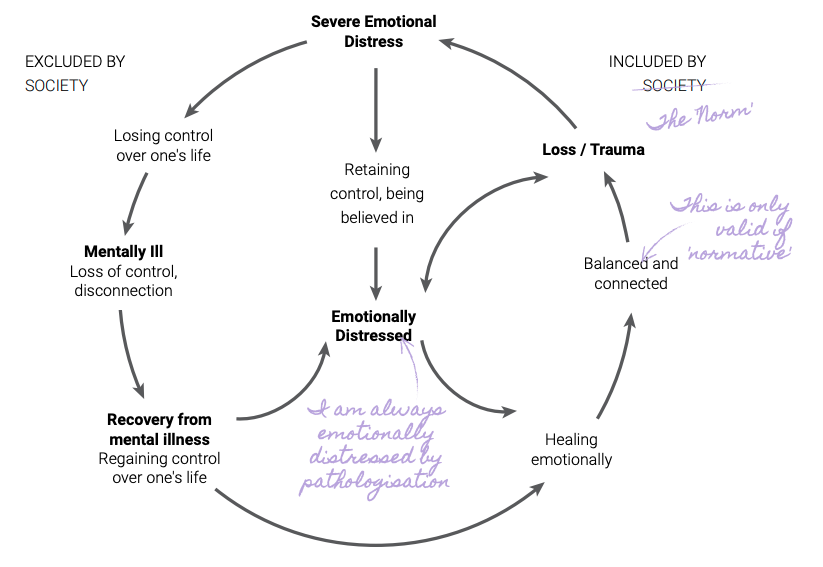

The conventional approach to ‘care’ views persons with mental health diagnoses in a linear framework: diagnosis/mental illness -> care-based (expert-led?) intervention -> remission or recovery. The #BridgeTheCareGap campaign has pushed us, both in policy and in praxis, to expand on the understanding of ‘care’ – to demedicalize interventions, decentralize support networks, to interrogate power, and to acknowledge people as the authorities on their own lived experience. To center communities in care, hear marginalized voices to care, to realize care is not a top-down system to be dispensed – it is a sum of all its participants: it is what makes us value human dignity, no matter who you are, or how you experience the world. We must set up the stage for us to question the very linearity that makes current mental health interventions exclusionary.

Looking at a care gap in mental health has presented an opportunity to challenge the perpetuation of a pathological, one-dimensional, mainstream narrative of mental health and has created a space to question the intentions of care. Who is the subject of care? Where is the space for user-survivors in care? What, for a person living with a psychosocial disability, is the desired outcome of care?

Neurotypicality as the ideal

The answers to some of these questions arise from the neurodiversity and disability rights movements. People with psychosocial disabilities have historically been marginalized because only the ‘normal’ (or neurotypical) mind is seen as a ‘successful’ mind. Mental health support and interventions have followed a script wherein the desired outcome is a person who is either neurotypical, or is as close as possible to ‘functioning’ as a neurotypical person. This leads to a prioritizing of certain markers of functionality: a 9-5 job as the most legitimate form of livelihood, a heteronormative family, class and caste specific social interactions, gender-appropriate social roles. These markers of ‘success’ are then viewed as the ideal outcomes of mental health interventions, which in turn reinforces other systems of marginalization.

What does care look like for a queer person with a queerer mind? While there is now increasing discussion and integration of/from marginalised genders and sexualities within mental health, the voice that is markedly missing is that of the user-survivor; of those that are neurodivergent. One must not only displace the centrality of heteronormativity, but also push back against a model of care that centers neurotypicality. Within the current care discourse, my lived experiences as a bipolar person do not inform the praxis of mental health. Having a standardized care model enforces a normative way of thinking about mental health; that there is only one correct way of functioning. If neurotypicality is the benchmark, then every battle I’ve fought to advocate for myself, build community, seek support, is erased. Acknowledging that neurological differences exist, that minds are a spectrum, necessitates that the lived realities of neurodivergent people are central to how we envision and articulate care.

If we commit to moving from a medicalized to a psychosocial model of care, then the intention of care must not be to ensure a person reaches a point where they no longer need care, but to re-envision what constant, consistent, community-led, survivor-centered, intersectional care looks like.

Critiquing the 'Empowerment Model of Recovery'