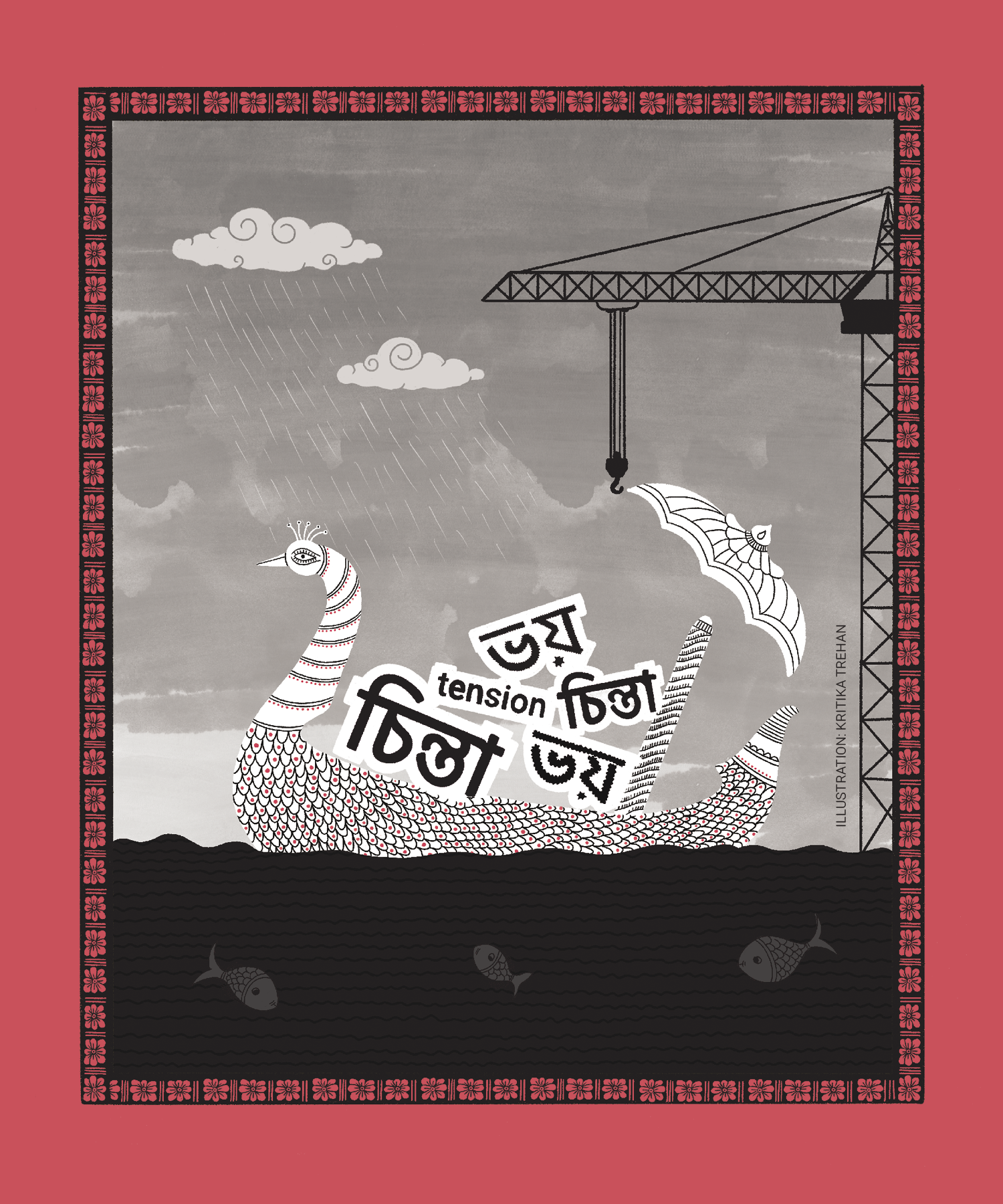

‘Chinta, Tension, Bhoi’: Expressions of distress in fishing communities

This isn’t the first time I’ve encountered such a use of “chinta”. Earlier that week, we were in the coastal areas of the state where, in May 2021, Cyclone Yaas had caused vast swathes to be submerged; boats, huts, nets, livelihood spaces had all been swept under surging waters. As the fisher union spoke to members about their livelihood issues, the latter often used the word “chinta”, or the furrowed eyebrows of those who didn’t spoke to their experience. During my fieldwork on shrimp near the coast, fnbarmers would regularly tell me, ‘Shrimp farming is like gambling. We’re tense thinking about whether we’ll take losses, or make profits.’ A fisher who had recently been beaten up by a group of drunken men on the beach while protecting his fishing gear did not want to file an FIR against his attackers because of “bhoi” (fear).

The drivers of such distress, even when specific to a person, often arise from the structural and social location of the individual; and may hint at more collective experiences of distress. For the fishers, it had been two months since the Cyclone, with welfare or compensation measures nowhere in sight. The state either lacked a true awareness of their losses, or had left the scope of the compensations too narrow, making it nearly impossible for them to resume livelihood activity. What the farmers referred to as “tension” was that in engaging in export-oriented shrimp production, their reliance on insecure land tenures, informal credit, and market fluctuations made the outcomes of their investments and efforts unpredictable. And the fisher’s “bhoi” emerged from a long history of engaging with the police as agents of the state, and of violence at the hands of locally powerful, landed-caste men. Ultimately, these powers-that-be represent an Indian society that fetishizes coastal areas as spaces of unbridled recreation, pushing fishers out of regions they have inhabited for generations.

Fishing communities cohabit the coast of West Bengal in sync with the sea. The sea is a source of food which, in living memory, has kept communities alive, through the Bengal Famine and during subsequent cyclones. The sea describes the geography: villages are well set back from the beach, livelihood and habitation spaces separated as generations of wisdom took account of storms in the region. The sea has topography: adapted to the slope of the seabed and the resulting tidal effects, the “behundi jaal” (fixed-bag net) drives the local dry-fish economy. The sea is seasonal: further north, where the Hooghly meets the Bay of Bengal, the nets change design during the monsoon months to catch ilish (hilsa). The sea is a nursery: along the Pichaboni river’s mud-flats, mangroves harbour fish breeding grounds. These forms of connection intimately bind the fishers to the sea – from where livelihoods, identities, and collectives emerge.

Other communities also inhabit the coast: originally, it was farmers who owned parcels of land and cultivated paddy; today it is communities owning shrimp farms, mechanised fishing boats, retail enterprises, resorts, and so on. In the post-Independence decades, fishers were usually either left out of the three-tier governance systems, or were not keen to engage with the process, largely (it is said) because of their seaward-based outlook. The resulting indifference of local governance decisions, from the Village Panchayat level upwards, to the fisher-sea relationship, combined with the absence of fisher representation, often exacerbates their precarious conditions. As capital-intensive processes involving the commodification of land (for cash crops, construction, SEZs) move towards coast and sea under the Blue Economy growth paradigm, fishers find chinta, tension and bhoi that emerging from their isolated location within the larger social structures in which they are embedded.

Illustration: Kritika Trehan

These structural locations not only shape fishers’ experiences of mental health, but also their access to medical care. As I write this, a fisher’s nephew is at NIMHANS, Bengaluru. We support them over the phone as they find themselves in an alien city; others accompany them to overcome language barriers. While NIMHANS is a publicly-funded and affordable medical institution, visits from West Bengal end up putting the family in debt each time. The fastest train from Kolkata to Bengaluru is regularly on surge-pricing and is becoming, with the privatisation of the railways, financially unviable. Slower trains make the journey with their child hard, given the heat and crowding. The Covid-19 pandemic further exposes the travellers to severe risk each time, even as the related lockdowns have plunged the already precarious fisher communities into debt. Non-democratic policy changes in state fisheries policies for fishing communities made during this period have further intensified their marginalization, which already has a long history. The climate-crisis has reduced fishing days and fish availability; annual cyclones now regularly disrupt fishing seasons, and inflict an unending cycle of financial losses. Together, these realities reflect both the biopsychosocial drivers and the constraints in accessing medical care that fishing communities experience.

Returning to the restaurant table: the fisher encourages the younger person to visit the beach with him sometime. He says he regularly walks along the beach when he feels overwhelmed. The younger person resists: ‘I have depression,’ they say, ‘I need medication and therapy to help me survive.’ The fisher ponders this, and says he’s never known that form of care, it is new to him; however, walks on the beach help him – he sees the sun rise, feels the sand under his feet, speaks to other fishers, giggles at the auction-site bargaining, embraces the emptiness of the beach at that early hour. And in that moment, ‘mon ta halka-halka hoye jaaye’ (‘the mind becomes lighter’). I take a moment to realize what he is saying: he isn’t prescribing a walk on the beach as a cure for depression; instead, his sharing this experience of mental distress from the margins, where he and his people reside, might offer an opportunity to find solace and support. There might be a chance here to explore how mental health in a situation of climate crisis, depleting seas, violent state policies, displacement, caste locations, and gendered lives, is affected and articulated, and how mental distress may be experienced concomitantly with one’s structural location in society. On the other hand, in his listening to the younger person, there is perhaps also a nod towards how, until such time as power asymmetries are overcome, there exist avenues of care where chinta, tension and bhoi need not be constant companions.

To listen to this essay, click here

Click here to download the full version of ReFrame IV

_________________________________________________________________________

Reference:

(1) ‘Blue Economy’ is an emerging concept which encourages better stewardship of our marine and aquatic (hence “blue”) resources so as to contribute to food security, minimize and adapt to climate change, and generate sustainable and inclusive livelihoods. When linked uncritically to “growth”, it sometimes becomes a paradoxical phenomenon. “Occupation of the Coast: The Blue Economy in India (2017).” Update Collective, Nov. 2017, updatecollective.wordpress.com/2017/11/21/occupation-of-the-coast-the-blue-economy-in-india-2017/.

“These structural locations not only shape fishers’ experiences of mental health, but also their access to medical care.”