The Atmiyata Story

Centering community as a resource

challenges in rural mental health

Approximately 70%-90% of the Indian populace does not have access to mental health treatment and care1. It is safe to say that these services are disproportionately available in urban areas; the mental health care system in rural India has all the shortcomings and failings of India’s rural physical health system. These include an insufficient number of trained health care providers, poor quality of available services, the need to travel long distances to avail of any service at all, and the exorbitant costs usually involved. The National Mental Health Survey of India 2015-16 estimates spends of Rs 1000-1500 per month on travel just to access mental health care. Adding to the psychosocial stressors for rural communities are multiple barriers to accessing education and social benefits, besides shelter and livelihood vulnerability due to the vagaries of climate. The “treatment gap” construct, with its biomedical focus, is inadequate for addressing these challenges, and exploring solutions for rural mental health.

Mental health issues are clearly linked to the psychosocial sphere, and can adversely affect participation in everyday social, work, family activities. It is important, then, to go beyond a “symptom reduction approach”, and work towards social inclusion via multiple pathways – such as employment, skills training, community education, and community support. While the prevailing treatment gap model erases this range of interventions, the “mental health care gap” construct proposes to combine the treatment gap approach with psychosocial care interventions, and also to take on board physical care gaps and needs for those living with mental illness.

mental health mitras and champions in communities

A rural mental health program called Atmiyata, currently run by the Center for Mental Health Policy and Law (CMHLP), employs all these strategies. It trains and develops the capacity of two tiers of community volunteers (“Champions” and “Mitras”) to identify and provide primary support and counseling to persons with emotional stress and common mental health disorders, and make referrals to the public health system in instances of severe mental illness. In order to reduce stigma and create awareness about mental health and well-being, both sets of volunteers work with existing self-help groups, farmers’ collectives, the Sarpanch and Gram Panchayat leaders, Anganwadi workers, ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) workers, Primary Health Centre staff, and others who are trusted and respected in the community.

Atmiyata Champions are given smartphones loaded with the Atmiyata app, which contains training materials as well as films meant to build community awareness about issues related to distressing everyday social situations: domestic violence, alcoholism, unemployment, spousal conflict, etc. The films can be shared via Bluetooth, encouraging wider discussion and helping depathologize the subject of mental health. This focus on psychosocial stressors, common causes of distress versus the biomedical approach is critical – whether in trainings, providing services, or the type of language used.

The Champions receive in-depth training, and provide interventions that include evidence-based, lowintensity counseling techniques such as active listening, problem solving, and behavioral activation—a therapeutic intervention that is often used to treat depression. They are also trained in facilitating access to social benefits such as pension allowances, disability benefits, unemployment benefits, besides providing information about social benefits available for caregivers2 . They also make referrals in cases of domestic violence and substance abuse, for legal aid, shelter homes, and employment generation. Atmiyata Mitras (Friends) have a different role – they work to identify distress and reduce stigma, while building their community’s understanding of mental health.

For persons who might require further help, Atmiyata leverages the District Mental Health Program by facilitating referrals for mental healthcare needs to public healthcare facilities and district hospitals, as well as to relevant district authorities in the public health and social justice system.

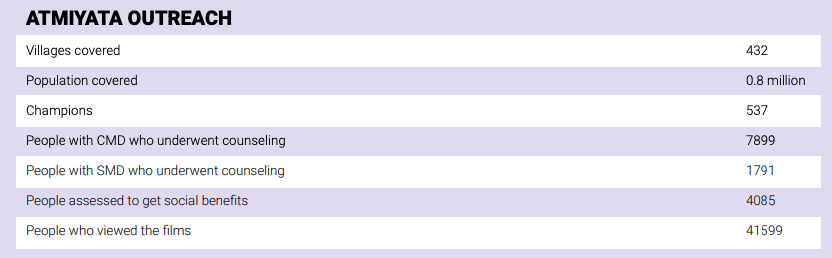

Atmiyata Outreach

communities are experts in their own contexts

Atmiyata is premised on tenets of community-based mental health that have informed rural mental health initiatives for some decades now. It shares similarities with other programs – like the Goa-based MANAS that trained rural community mental health workers to work alongside primary care physicians and mental health specialists, or the initiative in rural Pakistan that trained primary health workers to address post-natal depression3,4.

Yet Atmiyata has some distinctive features of its own: the Mitras are informal caregivers and community members, not primary health workers – an aspect that moves away from task-shifting, and redelegates specific care services to trained non-specialists. This allows for a high level of intervention by individuals who have a close connection with the social fabric of the place, share the living circumstances of persons needing care, and are able to communicate about mental health using contextspecific and accessible language. The program is distinctive also in its use of low-cost smartphones to enhance learning, build awareness, record feedback, and evaluate psychosocial interventions. Such recorded evidence is key to looking not only at scalable models of community mental health but also at discovering better ways to move on from the treatment gap model and to articulate more relevant approaches to the complexities presented by mental health care gaps in rural India.

Additionally, Atmiyata’s reliance on informal care by trained volunteers from the community lowers program costs, and helps in building trust. It effectively means that communities work to support their own members, thereby increasing community cohesion and resilience. Community stakeholders being involved and centered in the training and evaluation processes both enriches the program, and makes possible a sense of community ownership.

The Atmiyata program provides community, primary, secondary and tertiary care, even as it harnesses the public health system for specialized care. The underlying principle is that because the public health provisions are mandated by law, it is more cost-effective and sustainable to strengthen these public services than to turn to private or other expert-led services. The Champions and Mitras use a well-established referral chain, and carry out followups with psychiatrists working at the district level5 . This ensures timely diagnosis of mental health issues, and adherence to treatment in case of severe mental illnesses – thus bridging the gap between the shortage of trained mental health professionals and unmet mental health needs in rural India.

“COMMUNITIES WORK TO SUPPORT THEIR OWN MEMBERS, THEREBY INCREASING COMMUNITY COHESION AND RESILIENCE”