Articulating Sexuality from the Margins

Mental health practice usually approaches sexuality as an interpersonal matter between the individuals concerned. Matters of love and intimate relationships are seen as belonging essentially to the private realm. However, when the freedom to love is curbed, love is forced into the position of being about exercising a right. Any love that arises from queer sexuality, or crosses caste or community boundaries, is considered to be deviant – deviating from the norm and such non-normative expression is severely punished.

Sexuality, thus, cannot be understood solely as a private matter between the individuals concerned. Sexuality is a social construct, to which everyone is expected to subscribe, conceptualized strictly in terms of heteronormativity – which insists upon heterosexuality as the only legitimate sexual orientation. Within this system of heteronormativity, gender is constructed as a binary –male and female – with distinct gender roles that are rigidly enforced (Shah, Merchant, Mahajan, & Nevatia, 2015). It is mandated that sexual relations may happen only between these two genders and, further, only within the institution of a monogamous marriage that has the purpose of procreation to fulfill. To love in a non-normative manner becomes, then, a subversive act.

A working definition of sexuality by World Health Organization (WHO) says it is:

“…a central aspect of being human throughout life [that] encompasses sex, gender identities, and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. Sexuality is experienced and expressed in thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviours, practices, roles and relationships. While sexuality can include all of these dimensions, not all of them are always experienced or expressed. Sexuality is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, legal, historical, religious and spiritual factors.”

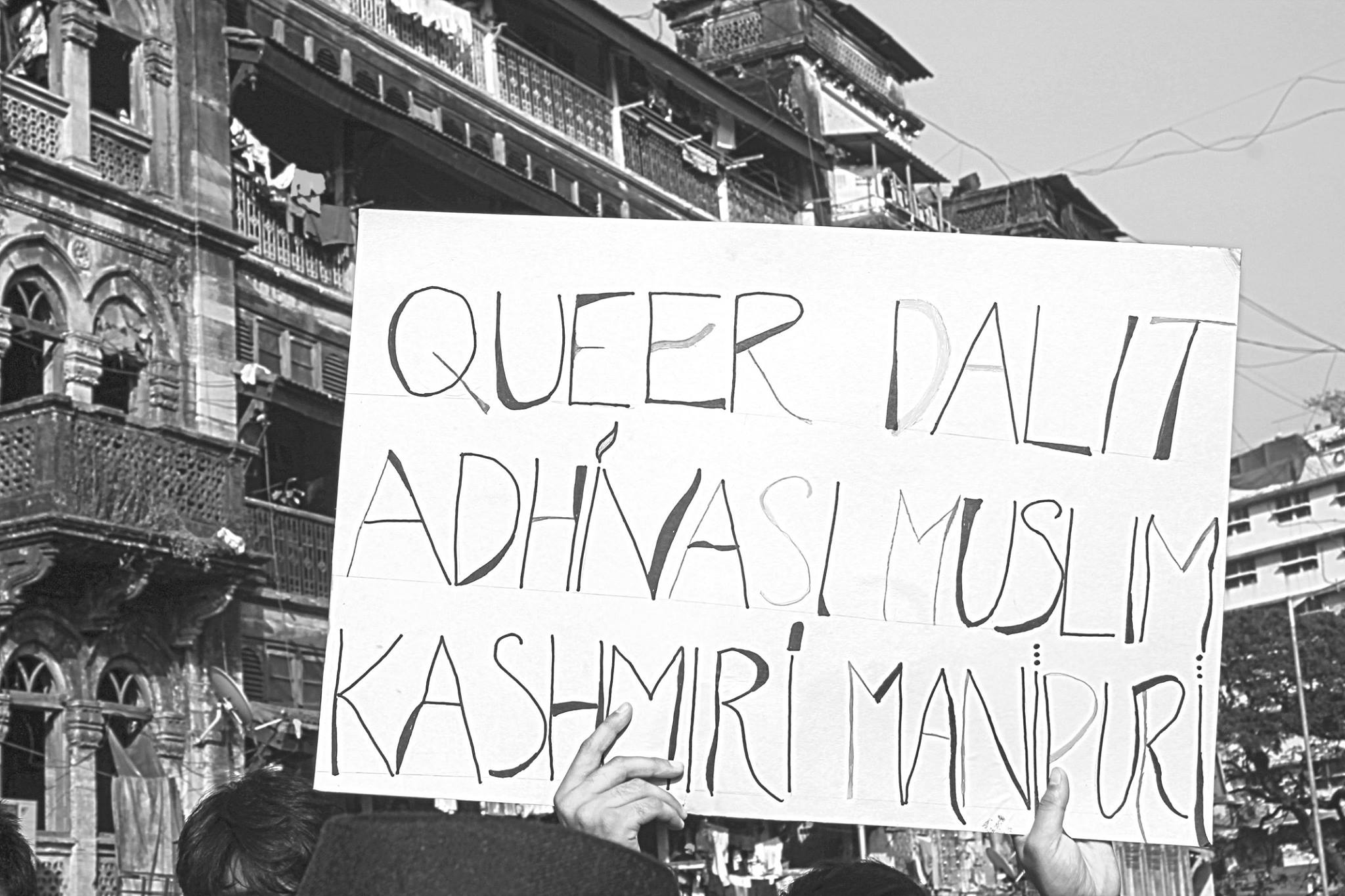

This definition allows for a multiplicity, diversity and fluidity of expressions and experiences in the realm of sexuality, gender, and relationships. However, this vast spectrum of possibilities is not equally visible – or accepted – in all cultures. There often exists a hierarchy, created and maintained by heteronormativity, and by the gender binary. Feminism critiques these hierarchies, and the unequal power relations they perpetuate. Just as patriarchy, casteism, racism, ableism are interrogated as social structures that presume the superiority of certain realities and oppress all others thereby deemed inferior, heteronormativity and the gender binary are critiqued as structures that oppress all non-conforming sexualities and genders.

Heteronormativity is upheld at the expense of non-heterosexual sexualities and non-binary genders. All non-normative realities are marginalised by this overarching norm. The effect of such marginalisation is often deleterious. “Individuals whose behaviour stands high in this hierarchy are rewarded with certified mental health, respectability, legality, social and physical mobility, institutional support, and material benefits. As sexual behaviours or occupations fall lower on the scale, the individuals who practice them are subjected to a presumption of mental illness, disreputability, criminality, restricted social and physical mobility, loss of institutional support, and economic sanctions.” (Rubin, 1984).

A variety of non-normative choices and intimacies that exist across the spectrum of sexualities do not fit the traditional marriage or family therapy frameworks. Norms are being broken daily, and people’s identities, desires and relationships are far too varied and complex to be squeezed into the narrow band that the heteronormative allows. However, under the garb of morality, society often punishes people who deviate from the norm. They experience distress, isolation and shame, with mental health implications such as depression, self-harm, substance abuse and minority stress. There is an urgent need for mental health practitioners in India to recalibrate our practice in order to make it an affirming space for a far wider range of lived realities to be expressed and validated.

To start with, it is important that mental health practitioners recognize heteronormativity and the gender binary as social constructs, and challenge their ‘naturalness’. We need to develop perspectives that question prevalent notions of the ‘normal’ and the ‘legitimate’. We must broaden our understanding of sexualities, and learn from the articulations of those on the margins. In the context of largely unquestioned social and cultural norms, feminist and queer voices provide critical counter-narratives that can help us recognize our internalised normative value frameworks, and make the necessary changes to our practice, in order to develop affirmative ways to engage with diverse sexualities in the field of mental health.

References:

Menon, N. (2012). Seeing Like a Feminist. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 36(1), 38-56.

Meyer, I.H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 129(5), 674-697.

Rubin, G. (1992). Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. In: Vance, C. S. (Ed). Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality. (267-293) London: Pandora.

Shah, C., Merchant, R., Mahajan, S., & Nevatia, S. (2015). No Outlaws in the Gender Galaxy. New Delhi: Zubaan.

“Norms are being broken daily, and people’s identities, desires and relationships are far too varied and complex to be squeezed into the narrow band that the heteronormative allows.”