The Need for a Rights-Based Lens in Education

Gender and sexuality in medical curricula

neutrality and objectivity are myths

The field of medicine has been critiqued for its gender biases, and for not considering the social determinants of health conditions. Gender bias permeates many aspects of medicine in India: clinical practice, research, health program delivery, and – not least – medical education. In curricula, the male body is the norm; the framework heteronormative. The women’s health movement in India has long been highlighting the complicity of modern medicine in continued gender-based oppression, and its lack of gender parity, whether in gynecology, general medicine, or mental health. This complicity is evident, for instance, in the medical misconceptions that lead practitioners to prescribe marriage as a solution for menstrual pain and other health conditions. Or in how doctors are conditioned to assume that persons who are not married are not sexually active. Or the belief that producing progeny after marriage is necessary for a healthy life.

The edifice of mental health and psychiatry in India has been particularly responsible for pathologizing non-normative genders and sexualities. Homosexual men were criminalized, incarcerated, or administered aversion therapy. Women, too, were attempted to be “cured” through ECT, and given punishments such as chemical emetics. Other medical disciplines learned from these measures, and there were even surgical interventions (including hysterectomy, ovariectomy, clitoridectomy, castration, etc.) to “cure” homosexuality. Such discriminatory structures typically focus on “cure” rather than “care”.

How do we challenge these pathological representations of LGBTQIA+ lives, and systemically counter such a legacy of violence and discrimination, in mental health and medical practice today? This is no longer an ethical imperative alone, it is now also a legal one. The Mental Health Care Act 2017 required medical professionals to affirm the rights of persons from communities marginalized by gender and sexuality, and to develop and provide appropriate services. And the National Health Policy 2017 acknowledged the crucial role of social determinants of health, and the need to address these urgently in health services. Then in 2018, the Supreme Court read down Section 377 of Indian Penal Code, effectively decriminalizing consensual same sex relations between adults.

However, despite these legal and policy changes, the old social dynamics are still at play. Medical professionals and their frameworks, which continue to be largely cisgender and heteronormative, come backed by tremendous power and privilege that greatly influence practitioner-client interactions. The alternative, on the ground, would be for doctors, health care providers and MHPs to be responsive to the specific needs of persons with marginalized sexualities and genders. Their sexual health and reproductive rights must be recognized and respected by the health system. This signals an immense need for sensitive gynecologists, endocrinologists, surgeons, besides MHPs – so that, for instance, trans persons desiring specific medical interventions might access them safely and securely. The overarching need is for radically altered medical and mental health syllabi, so as to include issues of gender and sexuality in all their complexity.

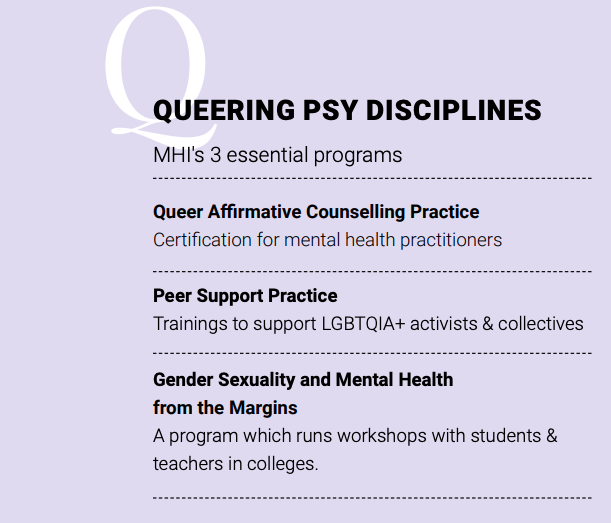

QUEERING PSY DISCIPLINES: MHI's 3 essential programs

incorporating lived realities into curricula

In 2017, CEHAT (Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes), along with trained medical faculty, carried out a review of the MBBS curriculum across the disciplines of Community Medicine, Gynecology and Obstetrics, Forensic Science and Toxicology, Medicine and Psychiatry. Among their findings: “sex” was not distinguished from “gender”; concepts of sexuality, sexual orientation, or of gender identities other than man or woman were missing – despite multiple health concerns related to sexuality being raised in health settings. Mental health implications and interconnections were conspicuously missing. The review project led to gender-integrated modules being designed to redress the knowledge gaps, with specific components on understanding gender and sexuality, sexual health, and the varied needs of different communities.

However, these modules, which foreground a rights-based, affirmative approach, can only be integrated into medical education as well as clinical practice through an in-depth training of educators. With MHI’s support, CEHAT plans to facilitate their delivery in three medical colleges in Maharashtra, reaching a minimum of 25 medical educators. Also, as part of the project, evidence will be collected on the health system’s existing responses to LGBTQI persons seeking health services, and medical educators’ attitudes towards the health issues of LGBTQI communities.

Project goals include making the modules more effective through training at least 30 psychiatry medical educators in the selected colleges for competency to teach as well as deliver gender sensitive clinical care and mental health services. Also being developed is a three-day course that focuses on understanding gender and sex, intersectionality, discrimination, physical and psychological health consequences, and building related skills. All these training programs will be delivered to medical educators across medicine, psychiatry, gynecology, forensics, and community medicine departments.

The project will also work to facilitate gender sensitive psychiatric care by assisting in, and documenting, the implementation of clinical protocols, and collating evidence for best practices. This stage will have two advisors from MHI’s Advisory Board, a mental health professional and a queer-identifying user-survivor, as we believe that lived experience and knowledge from the margins must be foregrounded in any such initiative. Affirmative health practices must not just take on board marginalized narratives; they call for fundamental changes in methodology as well as praxis.

“DISCRIMINATORY STRUCTURES TYPICALLY FOCUS ON “CURE” RATHER THAN “CARE””