Creating a Culture of Embodied Activism for Mental Health Professionals

As mental health professionals who want to ensure therapeutic spaces are rooted in social justice, we have to contend with various oppressive systemic ideas, policies, and teachings. How, then, do we unpack the Brahmanical, cis-heteronormative, as well as class-, education-, and ability-based privileges that feed into the individualized, internalized framework of mainstream psychology, so as to incorporate more contextual, justice-based lenses in our work? This article attempts to lay out how we, at Pause for Perspective, are navigating these challenges, and to explore how training spaces for MHPs and community workers can inculcate skills to help them discern and unpack structural determinants of mental health, through embodied activism and advocacy.

mindfulness: a collective practice rooted in compassion

We start by attuning our minds to our bodies, to become aware of and make space for the ways in which our bodies are impacted by – and respond to – structural factors. Mindfulness is a practice for cultivating intentional awareness of experiences unfolding within and around us, encouraging curiosity and an openness to leaning into each moment and noticing our sensations, emotions, thoughts. As a clinical, therapeutic modality, mindfulness has become a buzzword in recent times, and (not unlike mainstream psychology) commonly follows a westernized, individualized model. It offers tools for emotional regulation, managing stress, allowing difficult thoughts and feelings to pass. While these are important contributions, we find it essential to recognize that justice and compassion have, historically, been grounding principles of mindfulness practice in India.

Mindfulness has a complex history in the Indian context, originally deriving from the Buddhist tradition of “sati” (awareness), and travelling to the West where it became an evidence-based approach in Psychology. As it makes its way back to India in its psychologized form, it becomes essential to reconcile it with existing traditions of Indian Buddhism – most notably, Dr BR Ambedkar’s interpretation of Buddhism as a practice that can amplify the Dalit movement to annihilate caste and create a compassionate society. Ambedkar founded Navayana, the “New Way”, as a sect of modern Indian Buddhism which interpreted “dukkha” (suffering) as a collective, social suffering that was a result of historical marginalization and unequal systems of power. He envisioned “Nirvana”, then, as a process of collective and social transformation rather than a purely individual pursuit. We find this framework to be extremely supportive of our own mindfulness practice, in which the experience of “autopilot” – the flight, fight, freeze, and fawn,, responses in everyday life – is understood as a result of collective suffering due to that which fractures our body-mind-community relationship, and not simply as an individual, internal experience. Sensations of discomfort, pain, and so on, that show up during mindfulness practice, are seen as the body’s response to the world – as sensations that inform us of what is important to us, and not simply to be passed over, or regulated.

By keeping the practice trauma-informed and inclusive, by offering alternatives, and co-creating what mindfulness can look like for each person, we make this an activist practice; we cultivate it not as a way to be better adjusted, but instead to inform ourselves of how our body responds to prevailing systems and conditions, in order to be able to respond in ways that best align with our hopes for our body-mind-community.

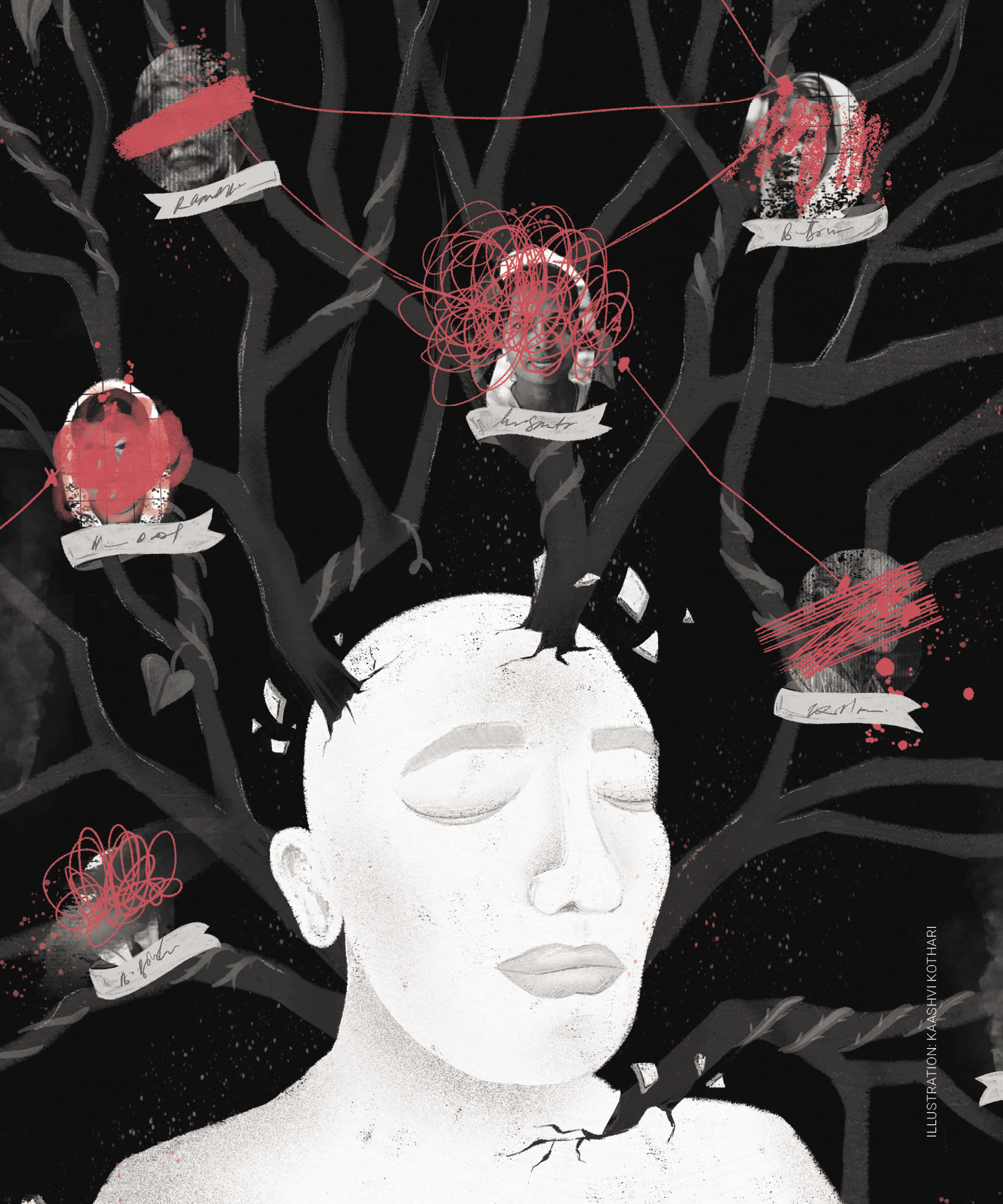

Illustration: Kaashvi Kothari

embodied activism in training spaces

‘While we see anger and violence in the streets of our country, the real battlefield is inside our bodies.’

—Resmaa Menakem

With increasing research, it's becoming evident that structural determinants like gender, sexuality, class, caste, race have long-term, inter-generational impacts on our bodies: we inherit bodies that store trauma. Our nervous systems are primed to react to others’ nervous systems from a place of survival and self-protection rather than connection. Thus, the mere cognitive understanding, or discourse, of systemic oppression and intersectionality is not enough to transform our learnt and habitual responses that maintain the very inequalities from which we wish to break away. Embodying this work allows us to sense how the nervous system expresses the discomfort of our privileges, the ache of our traumas and oppression, and the resulting responses of fight, flight, freeze, and fawn. Leaning into these sensations, along with their associated emotions and thoughts, allows us to embody and express our knowledge in safety; heal with the collective, and heal the collective as well.

We build this approach into our Integrative Mindfulness Based Practices Training (IMBPT) program that introduces formal and informal mindfulness practices. As we learn to notice and stay with sensations and body responses, a range of possibilities becomes accessible to us. The nervous system, slowing down, is able to access cues of safety that enable us to step out of habitual patterns and gain the space to respond in ways that are aligned with our values. Additionally, we become familiar with how our experiences of privilege and oppression show up in sensations of discomfort, heaviness, tightness, and aches. Becoming aware of our sensations allows us to step away from the stories reinforced by dominant systems, and to acknowledge and center people’s lived experiences.

An example of such work may be seen in a recent, supervised session with our collective of therapists who have completed different levels of the IMBPT program. We asked everyone to notice what happened in their bodies as they heard stories about Dalit, Adivasi, and upper caste clients. Our anti-caste commitment makes it important to have therapists who can discern how bodies hold stories of oppression and of privilege differently. Sitting together and recognizing the nuances in moment-to-moment responses helped us unpack the emotions and thoughts around privilege and oppression arising in the therapists’ bodies. As a team of AFAB (assigned female at birth) persons – some queer, some cis-het, mainly upper caste and of different religious identities – we soon became aware of our instant responses when it came to understanding people from one's own oppressed locations (gender, sexuality, and so on), and of how we typically overlooked oppressions caused by our privileged identities (particularly caste). We realized how we tend to hold space in an overly sympathetic as well as apologetic way when we inhabit upper caste bodies, resorting to using therapy in its individualistic form (which focuses on challenging and changing the client’s thoughts and feelings, rather than taking on board structural factors). It became apparent how the privileged body of the therapist could impact marginalized bodies in therapy spaces.

In our work with various communities, this framework has been a useful starting point in working with those in positions of power. Conversations with stakeholders entail facilitating an understanding of what happens in the body when speaking of the impact of systemic inequalities within their communities. In noticing how anger, hope, care feel in the body, we begin to tap into nuanced ways of training people in power to listen to voices from the margins and to center these.

In grounding this work of advocacy within our bodies, the hope is to discover ways of relating to ourselves and the world that bring us ease, openness, and rootedness in our bodies, allowing us to sustain the work of activism and healing. We have found it to be a deeply enriching, sometimes painful, yet largely joyous journey, in which training spaces are held in embodied care.

Click here to download the full version of ReFrame IV

References:

(1) Senauke, Hozan Alan. “Ambedkar's Vision for India's Dalits.” Lion's Roar, Lion's Roar Foundation, 16 July 2020, www.lionsroar.com/ambedkars-vision/ . Accessed May 2021.

(2) Yusuf, Sadaf Rukhsar. “The Epistemological Bases of Ambedkar's Navayana.” Forward Press, 15 Aug. 2017, www.forwardpress.in/2017/08/the-epistemological-bases-of-ambedkars-navayana/ . Accessed May 2021.

(3) “Flight, Fight, Freeze ” are considered as the body’s responses to experiences of trauma and acute stress. These are described as physiological responses by our brain's autonomic nervous system, part of the limbic system that focuses on ensuring survival and safety (Monteiro, et al.). “Fawn”, coined by Pete Walker, has more recently been recognized as one of these responses, and includes being compliant – pleasing others as a way to survive, and as a response to threat in social contexts.

(4) Monteiro, Lynette, and Frank Musten. Mindfulness Starts Here: An Eight-Week Guide to Skillful Living. FriesenPress, 2013.

(5) Walker, Pete. “The 4Fs: A Trauma Typology in Complex PTSD.” Pete Walker, M.A. Psychotherapy, 2013, pete-walker.com/fourFs_TraumaTypologyComplexPTSD.htm . Accessed May 2021.

(6) Tippett, Krista. “ ‘Notice the Rage; Notice the Silence.’” On Being, 4 June 2020, onbeing.org/programs/resmaa-menakem-notice-the-rage-notice-the-silence/. Accessed May 2021.

“‘While we see anger and violence in the streets of our country, the real battlefield is inside our bodies.’”