This points to the importance of building mental health services that may be availed of easily by marginalized individuals and communities, and that take into account systemic oppressions based on caste, class, ability, age, region, gender, sexuality, religion.

Mental health becomes a fundamental human rights issue when we think about the necessity of informed consent, and also about the lack of general awareness with respect to options and rights. We need, then, to work towards — to be advocates for — reforms in law and policy in the area of mental health, from a human rights perspective.

Raising awareness around mental health necessitates that we see it in its psychosocial context rather than through a pathologizing lens. This involves questioning narrow definitions, seeing it instead as a spectrum ranging from well-being to common or severe mental health disorders. Such an accepting approach is sensitive and non-discriminatory towards realities arising from caste, class, ability, age, geographical location, religion, gender, sexuality, and other common axes of marginalisation, enabling us to embrace people with different mental health needs.

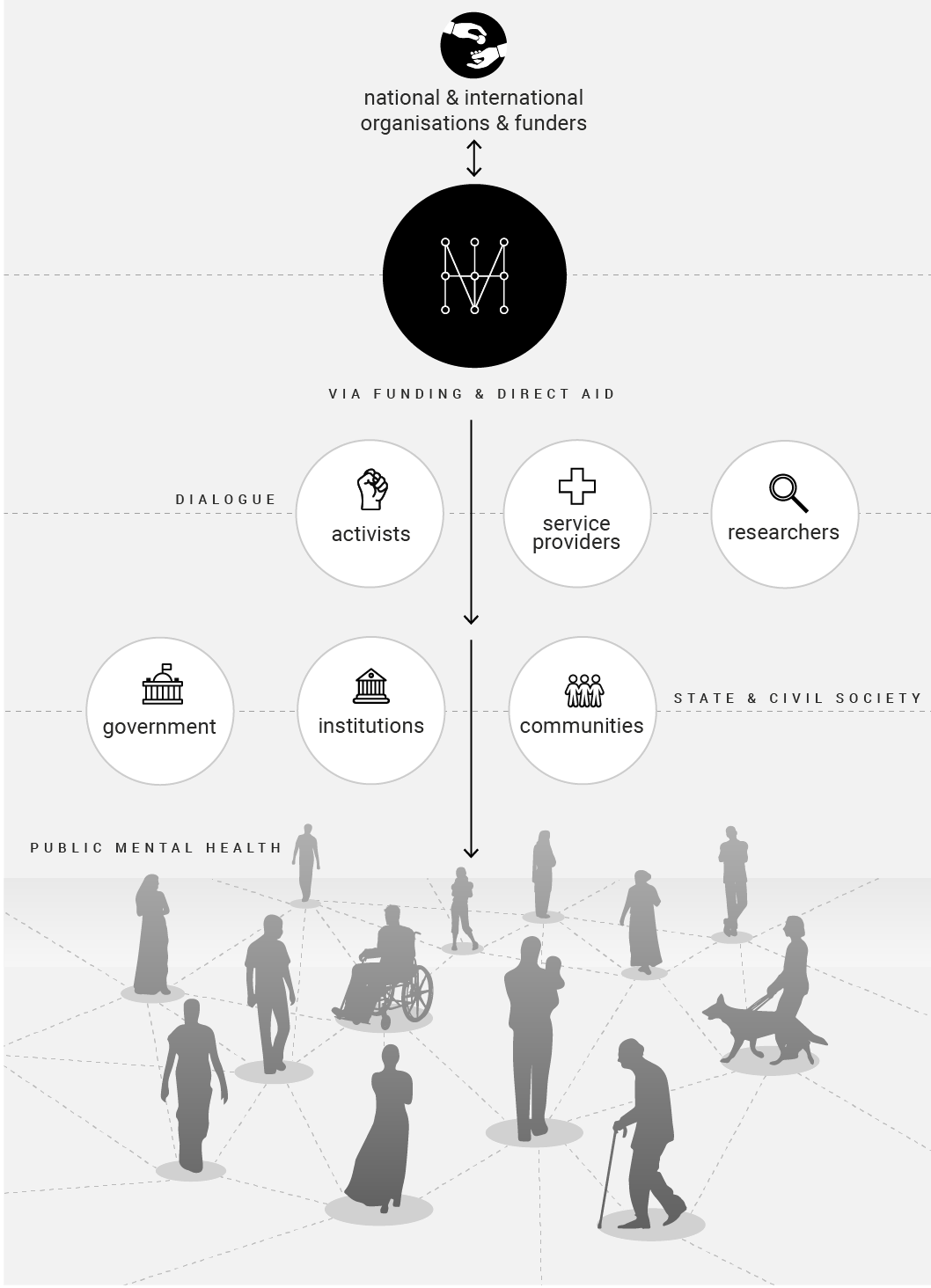

MHI works with partners to meet the mental health needs of individuals and communities through counseling and awareness initiatives. For a holistic and affirming ecosystem, legal and state institutions, educational and medical curricula, various public services, must all be nudged to play their roles as well. Also envisaged are a robust network of referrals between mental health providers, and linkages to other social services – thus ensuring a continuum of care, while also addressing the needs and challenges of carers.

An intersectional approach is based on an understanding of how systemic inequalities and structural barriers may, and often do, impact our mental health. Many studies have shown that marginalized communities are more susceptible to mental health stressors. We believe that mental health touches not only individuals, or families, but affects livelihoods and communities too, which must be taken into account when countering stigma, drafting policy, making services more accessible to all.

We work with the belief that individuals must have a say in their own mental health care, not just doctors – who often enforce a certain authoritative, and impersonal, recovery model.