Where Social Justice Meets Mental Health

Working with communities for collective mental health

realisation

I believe deeply in the idea that “The personal is political”, and shall therefore begin with a personal story. In 2003, after many difficult struggles, I passed my 12th Std exams with a First in Commerce – without any coaching, mentoring, or extra study materials. This was while living in a 10x10 ft room with eight other family members, and helping my father in his blacksmith’s workshop. They didn’t understand what these Board exams meant, or the importance of doing well in them. It was only when neighbors started dropping in, and saying I had stood second in my college, that my family realized I had achieved something. I hardly had time to congratulate myself, either, being worried about being able to continue with my studies with no money at home for that sort of thing. And my fears were fulfilled: my higher education ended for the want of 3,000 rupees. For almost a year, I held myself responsible, and would not look my friends and teachers in the eye. I lived with mental stress that was wholly internalized, never made visible; certainly, I had no access to any mental health resources. It was an unbearably painful period. I had demonstrated capability, aspirations, the will and readiness to work hard. Why had my journey then come to a halt?

Had I had counseling at that point, I would probably have been diagnosed with extreme nervousness or mild depression. But counseling was never an option, coming as I did from a nomadic, displaced tribal community and family for which social identity, security, and development remain faraway dreams. It is a community marked by addiction, unemployment, insecurity, illiteracy, and mental stresses related to all these factors. It was only later, when I entered the social development field, and built up my own understanding of caste, gender, and religious patriarchy, that I realized I was not personally responsible for my situation.

social hierarchies and collective expectations

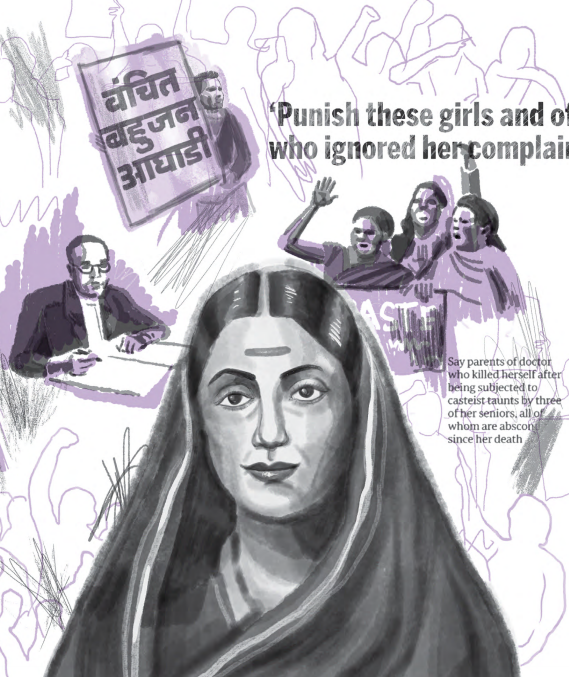

Social structures and systems create an environment where an entire community or society has “collective expectations” from a single person or group – for instance, a newlywed woman constantly being asked when she will be sharing the “good news” (pregnancy). Perhaps she maintains her mental balance for the first few months, but how long can she deal with the mounting pressure? Another example is that of the child who, growing up like every other, begins to realize she feels like a girl while everyone else believes her to be a boy. Will social expectations allow her to be herself? And if the child belongs to a vulnerable community, she is likely to face further violence. When someone is unable to live up to society’s collective expectations, it is common practice to isolate, excommunicate, denigrate them, or coerce them into meeting expectations – measures bound to affect their mental health negatively. Besides, when an individual’s mental health is affected, their family and community are not immune either. Collective social expectations, no matter if they stifle a person’s dignity, expression, participation, and development, follow a political design that ensures there is no danger to the existing Brahmanical patriarchy. The suicide of Dr Payal Tadvi is a recent example: a Bhil Muslim adivasi, she had overcome complex social barriers to become a medical doctor. Her colleagues at a Mumbai hospital, other doctors who had bought into the vicious caste rules that expect doctors to come only from certain powerful social strata, allegedly harassed Dr Tadvi till she took her own life. Viewing this incident through the lens of mental health, we may see how the doctors and the system that enabled such behavior violated Dr Tadvi’s right to both dignity and mental justice; cast her family into a situation of acute mental stress; and sent a clear message to the entire Bhil Muslim community – that anyone else trying to overcome caste barriers would be similarly treated – a threat with undeniable implications for collective mental health.

Many other situations playing out currently are affecting the mental health of entire communities: the heart-rending incidents of “mob lynching” of Muslims; extreme sexual violence against Dalits everyday discriminations based on caste, gender, religion, region, sexuality, and disability. Existing mental health services do not even begin to meet the growing need. The “treatment gap” approach, besides being biomedical, focuses on the individual rather than addressing the trauma and exclusion collectively experienced by communities.

It is necessary to link individual mental health to family and community. Our social and political systems must center the mental health of marginalized communities in ways informed by concepts of social justice and dignity. Our educational institutions, too, need to be part of a multi-sectoral plan to educate and empower youth and marginalized communities for better collective mental health.

constitutional morality

As in other law-based movements (the campaigns around the Domestic Violence Act 2005, or the Right to Education Act 2009, etc.), there is an acute need in the mental health movements for grassroots platforms, resources and leadership that facilitate community voices and articulations about collective mental health justice needs. India already has the progressive and inclusive Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHCA 2017), which all social institutions must engage with, and implement. This, along with adhering to the Indian Constitution’s values and Preamble, would help ameliorate situations where mental health is affected by disturbances in the social fabric. As Article 15 of the Constitution says, “No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition.” In other words, every person has the fundamental right to dignity, respect, development, and participation, which seems like a basic formula for mental health and social justice

“It is necessary to link individual mental health to family and community. Our social and political systems must center the mental health of marginalized communities in ways informed by concepts of social justice and dignity”