Pathways to Mental Health

Mental health in policy and praxis has multiple anchors

beyond the push and pull

Mental health has, historically speaking, been ignored in India’s political agendas. Psychosocial, intellectual and cognitive disabilities have either been described in pejorative terms, or proposed as cases for charity, thus perpetuating stigma and discriminatory practices. To give a brief perspective, 70%-92% of persons with mental illness who require mental health care either do not have access to services, or — if receiving services — cannot access quality care that is affordable, easily available, and satisfactory, which is referred to as the treatment gap.

India had 17·8% of the global population in 2016 but accounted for 36·6% of global suicide deaths among women and 24·3% among men. For women younger than 40, suicide is the leading cause of death, ahead of the maternal mortality rate; for men below 40, it is the second leading cause of death, after road traffic accidents. Despite the high incidence of mental health problems, estimated to affect 150 million Indians, the focus of the State has been centred on a “medical” model of care that is mainly institutionbased care.

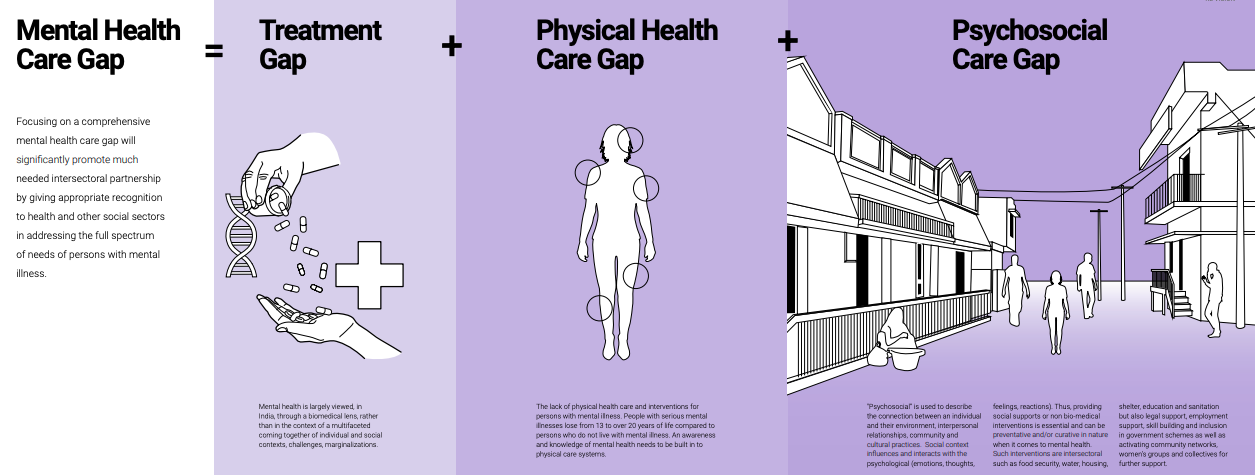

Even within existing mental health care, a dearth of mental health care professionals, and the lack of a human rights approach, together widen the “mental health care gap”. “Mental health care gap” is a purposive term, used to mark an ideological re-conceptualizing of the more prevalent “treatment gap”. The latter carries a medical connotation, and implies biomedical treatment (or lack of it) of mental illness. This “treatment gap” is often interpreted by policymakers, planners and researchers, as well as by non-professional stakeholders, as referring exclusively to curative clinical psychiatric interventions, thereby leaving out effective psychosocial interventions.

Defining the Mental Health Care Gap Construct

reformulation

“Care" is a relatively comprehensive term, which allows us to acknowledge how mental health is affected by, and may impact, various social, economic, and political factors. Mental health cannot be understood in isolation from people’s lives and contexts. The notion of a “treatment gap” frequently leaves out those psychosocial interventions that are almost always required by persons with severe mental illnesses that affect social functioning; the omission of such interventions impedes or delays recovery. “Recovery” indicates, here, not merely a reduction of symptoms , but a person-centric process geared toward their being able to lead their life in accordance with their own will. For recovery, we need to address a range of psycho-social interventions along with the medical care and treatment. A study on schizophrenia demonstrates a range of psychosocial treatments are also helpful, including family intervention, supported employment, cognitive-behaviour therapy for psychosis, social skills training, teaching illness self-management skills, assertive community treatment, and integrated treatment for co-occurring substance misuse.

The mental health care gap is also concerned with the physical health care gap, because of the frequent, yet highly unaddressed, physical comorbidity conditions and premature mortality of persons with severe mental illness. Persons with severe mental disorders (SMD) − i.e., schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, and moderate‐to‐severe depression − die 10 to 20 years earlier than the general population , which is often due to physical diseases that occur more frequently, are not prevented adequately, are not identified early enough and are not treated effectively. Despite this, little progress has been made to address physical health care and mental health care as a structured process of reform.

There is a relationship between non-communicable diseases (NCD) and severe mental health disorders which also needs to be addressed. A person's NCD symptoms can exacerbate mental health conditions, and at the same time, mental health conditions can be a risk factor for developing NCDs. In addition, individuals with mental health conditions are less likely to seek help for NCDs, and symptoms may affect adherence to treatment as well as prognosis. Research also points to premature mortality among the mentally ill who live in large asylums, and the millions of people with SMD who are currently detained in prisons worldwide, who are particularly exposed to chronic diseases (including, especially in low‐income countries, infectious diseases), poor nutrition, victimization, neglect, suicide and substance abuse.

Moreover, mental well-being is not a health issue alone, but also a development issue. People with mental illness are subjected to discrimination and stigmatization in their daily lives, bear a greater risk of physical and sexual violence, and tend to be excluded from developmental programs. Most people with mental illness face barriers not only in education and finding good jobs, but also in asserting their civil and political rights. Such exclusion and discrimination results in reduced income levels and poverty.

“Mental health cannot be understood in isolation from people’s lives and contexts”

Focusing on a comprehensive mental health care gap will significantly promote much needed intersectoral partnership by giving appropriate recognition to health and other social sectors in addressing the full spectrum of needs of persons with mental illness

compounded consequences

Research has shown that poor mental health is more likely to affect people who are at a social or economic disadvantage. A recent study concluded that, as income inequality increases worldwide, “we should expect worse mental health globally in the years ahead” and that the burden will most likely fall hardest on individuals who “already bear a disproportionate burden of mental health problems”. Mental illness affects employment, too, which is complicated by the fact that the cause-and-effect factor can work in both directions: unemployment may worsen mental health; and mental health problems may make it more difficult for a person to obtain and/ or hold a job. The employment rate of people with common mental disorders (CMD) is 60-70%, which is 10-15 % lower than for people not diagnosed with any mental disorder. The corresponding employment rate for people with severe mental disorders (SMD) is 45-55%. Poor mental health outcomes are associated with employment conditions, workers who perceive work insecurity, such as temporary contracts, or being employed with no contract, and part-time work experience significant adverse effects on their physical and mental health. Work conditions also affect health and health equity.

These statistics point to the remorseless, self-perpetuating cycle of poverty associated with mental illness in India. The poor are significantly more likely to experience mental health problems, and those with mental health problems are correspondingly that much more likely to slide into poverty. Inclusion of persons with mental illness as a vulnerable group that requires development assistance is therefore crucial.

Other social issues such as domestic violence, sexuality and caste also negatively impact mental health. Domestic violence has a long-term impact on the mental health of women. Women who are subject to violence can experience depression, panic, anxiety, nightmares, restlessness, eating problems, and other social dysfunctions. Alcohol and substance abuse, and suicidal thoughts and attempts are also common among women who face violence.

Till recently, existing as anything but heterosexual was a crime in India, which led to the social exclusion of sexual minorities. There has been little attention paid to the mental health needs of persons of nonnormative sexualities (and genders) who are especially vulnerable due to their experiences of being bullied, discriminated against, socially excluded, and denied basic rights such as access to healthcare. Similarly, caste is yet another determinant of mental health. Castebased discrimination and social exclusion impact the mental health of individuals who face violence, lack of support, trauma, and isolation.

We therefore encourage an alternative conceptualization of the gaps in mental health care, where Mental Health Care Gap = Treatment Gap (as currently understood) + Psychosocial Care Gap + Physical Health Care Gap. Closing the mental health care gap requires an intersectoral and intersectional approach by policymakers, who need to acknowledge that mental health care is a human rights issue as enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Soumitra Pathare is a Consultant Psychiatrist and Director of Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy at ILS. He has contributed to the WHO Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Soumitra has also helped to draft India's new mental health law and was a member of the Policy Group appointed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, to draft a new national mental health policy for India.

Jasmine Kalha has an M.Phil in Sociology from Delhi University and a Master of Arts in Social Work from TISS Mumbai. She has been associated with CMHLP since 2014, and is currently Programme Manager and Research Fellow for SPIRIT (Suicide Prevention and Implementation Research Initiative) a mental health program implemented by CMHLP in Gujarat.